It’s 97 degrees, and at Forest Hills Park, children sprint up the playground stairs and chase each other down the slides. “Tag, you’re it!” they scream. Like clockwork, when a few minutes in the sun have passed, they soothe soon-to-be burnt skin by running through a “sprayground” — water that mists from colorful metal tubes. When it is time for a breather, the kids head to the shade, where parents offer snacks and water bottles.

Less than 100 feet from the playground, a fence gate padlocks the entrance to the pool. On a typical summer’s day scores of people would crowd into the water. But today, the pool sits empty. No submerging and simmering down from the hot and humid air, it appears.

Forest Hills Pool is one of three public outdoor swimming pools in Durham, the others being Hillside and Long Meadow. Yet, on Tuesdays and Thursdays, none of them is open. Hillside is not open on Saturdays either. But on the days they are open, each is only available for swimming for four hours during the afternoon. On Saturdays, Forest Hills and Long Meadow are open between 9 a.m. and 1 p.m.

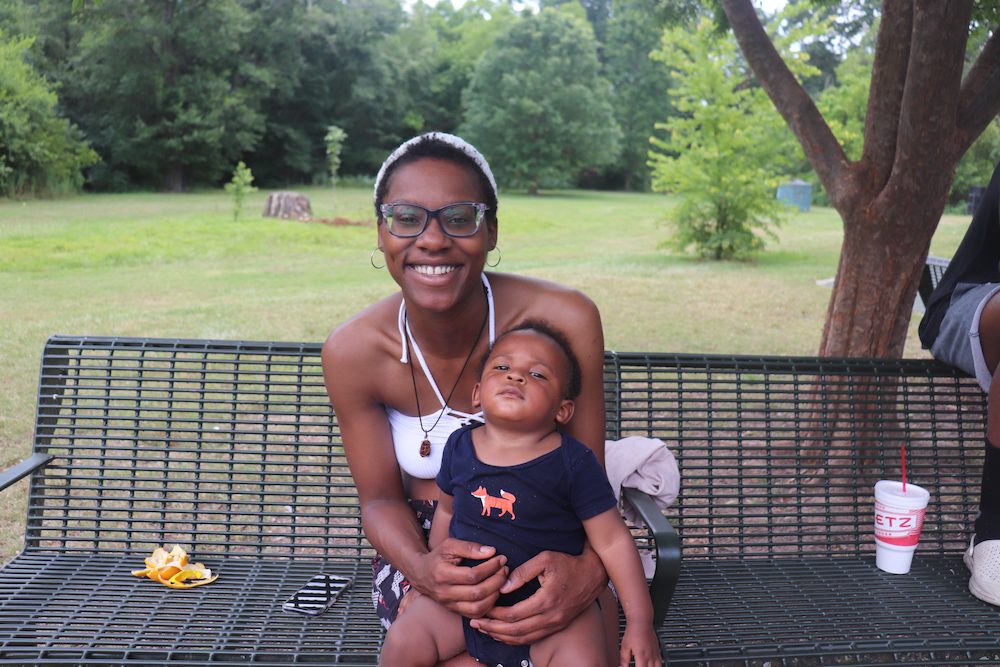

“That’s such a restricted time frame,” says Taylor McCarther, who recently moved to Fletchers Chapel Road from Greensboro with her two young sons and partner Ben. “Yeah, it’s kind of weird that it’s just that chunk of time. I mean, I get it. But not really.”

As she says this, her younger son, Kayden, tears up before he walks toward the shade.

“You’re the one standing in the sun,” she says playfully.

The city has seen temperatures soar beyond 90 degrees 10 times since July began. Staffing issues have hampered Durham since the outdoor pool season started in early June. There’s a lifeguard shortage — not just on the local level but statewide and nationally.

The American Lifeguard Association says the lack of lifeguards affects one-third of the nation’s pools. Pools in the three most populated cities in North Carolina — Greensboro, Charlotte and Raleigh — have found themselves understaffed.

Even some of the country’s major cities such as Seattle, Denver, Chicago, Houston and Boston have struggled with shortages.

“I recently learned that there is a city in Michigan that is paying $27 an hour to try and entice lifeguards to work for them,” says Jason Jones, assistant director of Durham Parks and Recreation. The average lifeguard salary in the U.S. is $13.94 per hour, according to Indeed.com.

To address the shortage, Parks and Recreation partners with Durham Aquatic School to provide free lifeguard certification training for participants 16 and over. It also offers a competitive salary. The city government website says that lifeguards for Durham pools make between $17.99 and $21.56 an hour, which Jones says makes it the highest pay for lifeguards in the Triangle.

He says no one has called his department to voice concerns about the reduced pool opening hours.

Jenny Rendon, who has lived in Durham for 18 years, used to take her children — who are 8, 9, and 20 months old — to the pool once or twice a week. But this summer’s restrictive schedule changed that.

“That’s one of the biggest things, that sometimes with those schedules and depending on the distance, for example, if I go to the….closest one, you know, it’s not [always] available on the day that I want to go take my kids,” Rendon, a homemaker, says.

“You know, some people don’t have enough personnel, staff, to run their places,” she adds, referring to the Department of Parks and Recreation. “So I don’t blame it on them.”

When swimming in a public pool is not an option, spraygrounds are an alternative. They are open seven days a week, for free, at four parks throughout the city: East End, Edison Johnson, Forest Hills and Hillside. Each operates between 8 a.m. and 10 p.m.

McCarther and her family have spent many days exploring water spots, such as Jordan Lake and the Eno Quarry. Since moving to the area, they have come to Forest Hills Park twice. They liked it because it is surrounded by a forest. The family has also been visiting other playgrounds around the city, seeking to get the children outside to play — and get wet.

As she sits on a shaded bench, McCarther, who is in her mid-to-late 20s and expecting her third child, watches children at the park play. Next to her lie orange peels and a red-and-white soda cup.

Her little boys are part of the crew of children making use of the sprayground this afternoon. The older one, Kellan, almost 4 years old, is an “outside child,”she says. He has “super-high energy, and playgrounds are always just perfect for him to just let all that energy out. Sun beating down on him, letting that energy out.”

Kellan runs around in a soaked red T-shirt that his mother says will be dried out by the sun. Kayden, 18 months old, stomps, chasing his brother in a navy blue fox-themed onesie and a diaper.

“They don’t need swim trunks,” McCarther says. “They don’t need any of the extra specialties. Like if it’s there, they’re ready to go—dirt, mud, water, sand—they love it.”

Above: With Forest Hills Pool (top) and other swimming pools open limited hours, Taylor and Kayden McCarther (center) seek out shade. Photos by Ana Young — The 9th Street Journal