When Gov. Roy Cooper tweeted out his plan to move North Carolina into Phase 2.5, his post garnered dozens of replies for and against the guarded decision.

“I want to say some unkind words,” one Twitter user wrote, “but I will hold it for the polls.”

The tweet’s poster won’t be the only Carolinian carrying coronavirus opinions into the voting booth.

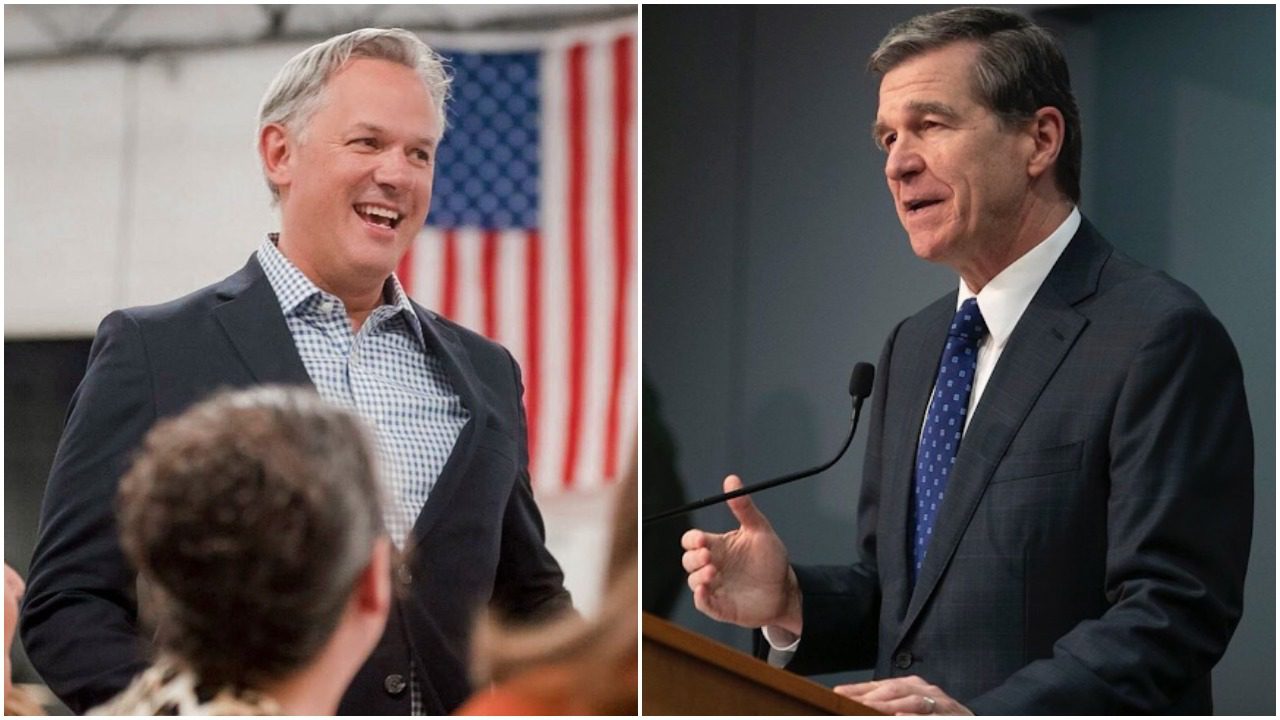

Cooper’s announcement comes during a governor’s race that has been dominated by COVID-19. The governor and his Republican opponent, Lt. Gov. Dan Forest, fall on nearly opposite sides of the spectrum when it comes to handling the pandemic. Cooper describes his approach to reopening as cautious and data driven. Thoughts and face unmasked, Forest has criticized him every step of the way.

Forest, 52, has served as North Carolina’s lieutenant governor since 2013, following a successful career in architecture. In the role, he acts as president of the North Carolina Senate and a voting member of the State Board of Education. Forest is also a member of the North Carolina Advisory Commission on Military Affairs, and serves as the chair of the Energy Policy Council and the Board of Postsecondary Education Credentials.

Cooper, the 63-year-old Democratic incumbent, won his office in 2016, narrowly defeating Republican candidate Pat McCrory. He served as North Carolina’s attorney general for 16 years prior.

The race could be tight. North Carolina is a swing state, and the Cook Political Report classified the governor’s seat as lean Democrat. The outcome may be determined by the success of Cooper’s continued coronavirus response.

Epidemiologists and public health experts say Cooper is making the right decisions. Ahmed Arif, an epidemiologist at UNC Charlotte, said Cooper’s incremental approach is what the state needs to avoid another spike in COVID-19 cases. But it’s not so simple, he added.

“It’s a difficult job for public health professionals to make a case when you’re fighting against an unseen enemy,” Arif said. “People can’t see in front of them how many deaths and infections they’re preventing when they follow the guidelines.”

Tomi Akinyemiju, an epidemiologist and professor of population health sciences at Duke University, is also wary of a new spike in cases as the state continues to reopen. She said she’s thankful for Cooper’s reliance on data-driven benchmarks as he leads the charge against the pandemic.

“We have to guide our decisions with data. Not with emotions, not with money, because at the end of the day we’re talking about human life here,” Akinyemiju said.

With scientists and public health officials in his corner, Cooper continues to slowly lift restrictions. “Governor Cooper is laser-focused on making sure we emerge from the pandemic even stronger than before,” wrote Liz Doherty, Cooper’s director of communications, in an email to The 9th Street Journal. “He’s relied on science and data to make difficult decisions,” she said.

And as he makes these decisions, Cooper is under the spotlight.

For months, the incumbent has given eagerly awaited press conferences as he manages the state’s pandemic response. Carter Wrenn, a longtime Republican political consultant in North Carolina, said that Cooper’s leadership role presents a challenge for Forest.

“The whole election is going to be a referendum on Cooper’s handling of coronavirus,” Wrenn told The Atlantic in May. “He’s got a big advantage in that he’s got a microphone. Forest has nothing compared to that,” he said.

Donald Taylor, a professor of public policy at Duke University with a focus in health policy, said that Forest is likely desperate for coverage. It makes sense for Forest to so vocally oppose Cooper’s handling of the pandemic, he said, because he doesn’t have many other options.

“I don’t think Lieutenant Governor Forest has any other case for press,” Taylor said. “There’s so much noise, there’s no way to break through. And he’s losing, so he’s probably doing the only thing he can.”

Despite all the attention on Cooper, Forest has been making waves on the campaign trail, drawing both support and harsh criticism for his in person campaigning. He’s held multiple events with crowds that exceed the limits outlined in Cooper’s executive order, and footage of the events show the vast majority of attendees not wearing face masks or social distancing.

The challenger poses for pictures with supporters, ignoring the CDC’s suggestion of maintaining six feet of distance. “We shake as many hands as we can,” Forest said in an interview with WXII news, at the site of an in person campaign event he held in August.

Nathan Boucher, a Duke University professor of population health sciences and public policy, said he thinks Forest’s extreme anti-Cooper messaging is the basis of his entire campaign.

“Forest has no platform other than being pro-Trump and anti-governor Cooper,” Boucher said. “Nothing that he says is intelligent. There’s nothing evidence based, there’s no plan.”

Forest’s campaign did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In contrast, Cooper is not campaigning in person at all. “I think the Department of Health and Human Services would tell anyone that if you’re having these kinds of gatherings, that you risk the spread of the virus,” he previously told reporters, referring to Forest’s in person events.

Republican Governors Association spokesperson Amelia Chassé Alcivar criticized Cooper for his remote method of campaigning, calling it “undemocratic,” The Charlotte Observer reported.

Forest’s often flagrant violations of public health recommendations resonate with voters who feel the threat of the virus has been over exaggerated, like the supporters of ReOpen NC, a group that has organized multiple protests against the state’s shut down orders and called for the impeachment of Cooper in July.

Cooper’s evidence based approach to reopening is likely garnering support for him in progressive areas of the state, Boucher said, such as the triangle area, Asheville and Charlotte. But “there are different North Carolinas within North Carolina,” Boucher said, and Cooper’s pandemic response is ruffling some feathers, especially in more rural communities.

Those opposed to Cooper’s handling of the pandemic appear to be in the minority for now. The vast majority of polls show Cooper leading Forest by at least 10 points. An August 11 poll conducted by Emerson College, however, has Cooper leading by just six.

The incumbent also comfortably leads the money race, easily outraising his opponent according to the latest campaign finance reports. The Committee to Elect Dan Forest reported it raised $2.4 million over nearly five months months ending June 30 and had close to $2 million in cash on hand then.

But the Roy Cooper for North Carolina committee announced in early July that it had raised about $6 million, and had $14 million in cash on hand on July 1.

In Cooper’s latest coronavirus press conference, he emphasized that taking the pandemic seriously will help get the economy back on track faster.

“Every time you wear your mask or social distance, you’re helping our statewide numbers so we can ease restrictions,” he said. “We help our economy by slowing the spread.”

Cooper also took a subtle jab at the North Carolinians who are not adhering to COVID-19 restrictions. “Most of you are showing you know how to fight this disease,” he said. “And most of you should be proud of yourselves.”

Taylor said he thinks North Carolinians have difficulty grasping what he believes it takes to reopen the economy safely. “North Carolina has been one of the epicenters of a false dichotomy, which is that you can deal with the pandemic or you can reopen the economy,” Taylor said. “The actual answer has always been that you reopen the economy by dealing with the pandemic.”

Forest and Cooper have been clashing over the handling of the coronavirus pandemic since it reached North Carolina in March. When Cooper first announced a ban on indoor seating for restaurants and bars, Forest responded with a press release, writing that the governor’s decision would “devastate our economy, shutter many small businesses, and leave many people unemployed.”

Forest sued Cooper in July over coronavirus related executive orders, claiming that the governor did not have the authority to issue the orders. Forest has since dropped the lawsuit, but their disagreement remains alive and well. In many ways, the North Carolina governor’s race embodies the economic health versus public health debate that has been simmering for months.

“I think everything should be open,” Forest told The Atlantic. “I don’t care about getting a virus.”. He said he supports issuing recommendations rather than mandates and believes businesses should be left to make their own decisions.

“I don’t think the government should lead with a stick,” Forest said. “It should lead with a carrot and allow these industries to have some personal responsibility and freedom.”

Boucher said he wishes Cooper and Forest could work together on leading North Carolina through this crisis. That might have made it easier for people to accept the tough realities of reopening, he said.

“Cooper has had to make some difficult decisions in the face of a lot of opposition, including his own lieutenant governor,” Boucher said. “I think he’s made the right ones for the people of North Carolina, but everybody gets hurt with every decision.”

In the era of COVID-19, North Carolinians are desperate for a leader they can trust. Those who support Cooper’s “dimmer switch” approach to easing restrictions will almost certainly not be voting for Forest come November.

But others fed up with economic hardship and pandemic fatigue may blame Cooper. For them, Forest represents the hope of reopening the state once again.