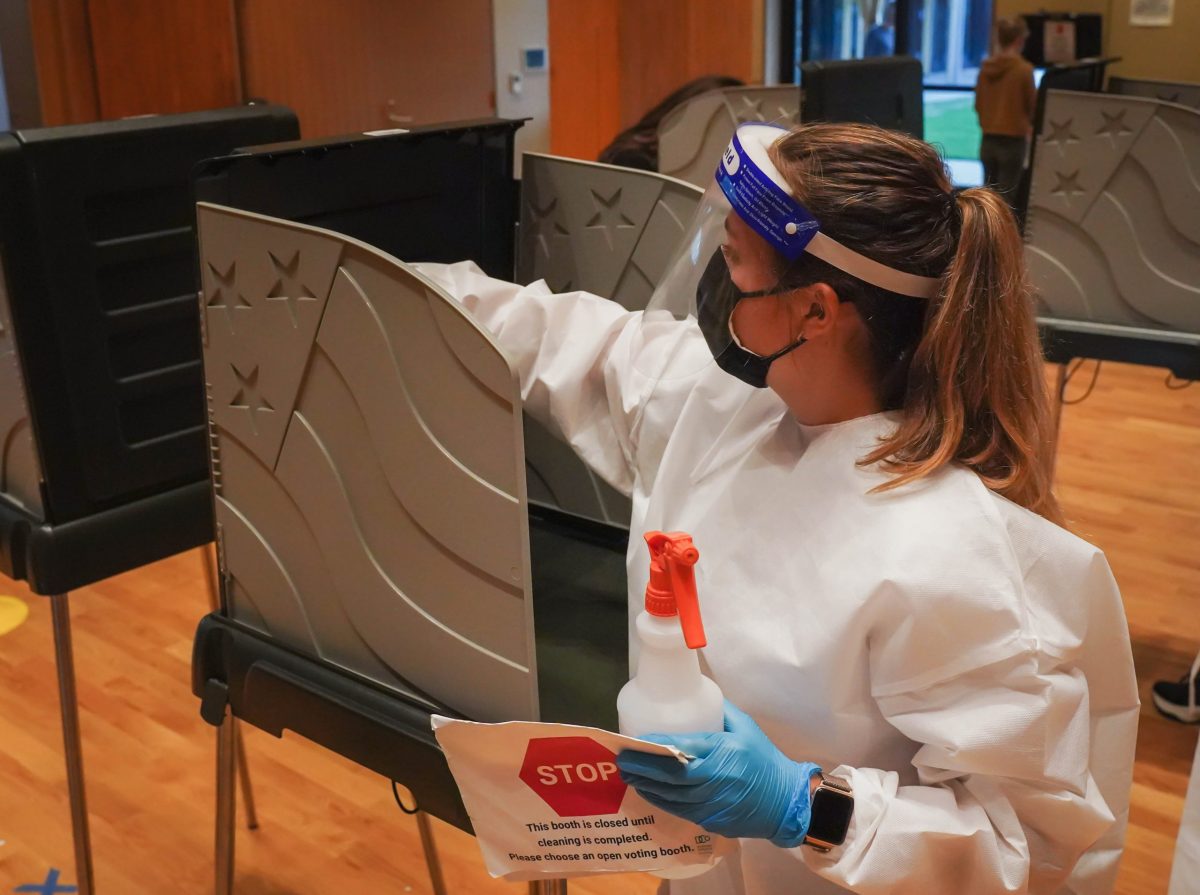

Wearing a plastic face shield, a blue surgical mask, blue gloves and a white surgical gown that reaches down to her pink running shoes, Maria Quiros looks like many of the health workers battling the coronavirus in hospitals across the country.

But this is no hospital. It’s the early voting site at Duke’s Karsh Alumni and Visitors Center. And Quiros’s job isn’t to heal the sick — it’s to protect thousands of voters from the virus.

Her outfit is a reminder that the coronavirus pandemic has transformed voting, usually no more risky than visiting the county library, into an activity that is potentially life-threatening.

“It makes everything feel very surreal,” said Emma DeRose, a Duke senior and volunteer poll worker who helped wipe down the voting stations with disinfectant. “Obviously, we know a pandemic is going on. But I think Duke is kind of in a bubble in a way. We’ve had a pretty low case count, and it doesn’t really feel that present. And then I think you get to the polling center, and you’re seeing these people, including myself, just all decked out, and it’s like ‘woah.’”

Voting, like going to the grocery store or to school, has become a stroll through a minefield. And, since early voting started in North Carolina on Oct. 15, Quiros, DeRose and others have kept voters safe with a wad of paper towels and a spray bottle of disinfectant.

According to an Aug. 14 memo from the North Carolina State Board of Elections, workers at voting sites are required to perform “ongoing and routine environmental cleaning and disinfection of high-touch areas” with an EPA-approved disinfectant for COVID-19.

On a recent Friday, Quiros stood at the left side of the voting room in Karsh. She had her dark hair in a bun, and her eyes scanned the booths. As soon as a voter left a booth, Quiros scurried over and began cleaning.

She started by wiping the bottom of the polling booth. Next, she cleaned one side, and then the other, finishing with a horizontal swipe along the front edge.

While waiting, Quiros also directed voters to empty booths or helped them follow the blue arrows to the spot where they could scan their ballots — she’s both the cleanup crew and stage director.

It’s tedious work, but Quiros is staying positive. She’s confident that the polling place is safe for voters.

“Because we are taking care of them,” she said.

Quiros said she has been working 12 hours a day since Oct. 15. She has help. There are 10 to 15 poll workers during each shift, and these workers rotate between various positions, from ballot tabulator to sanitation worker, said DeRose, who was greeting people and handing out pens.

“I think just us being very thorough with the cleaning provides a sense of comfort,” DeRose said.

This Friday afternoon, Quiros was accompanied by Kate Young, 72, who had started her cleaning duty at 1:30 p.m.

“You get used to it,” she said, referring to the protective gear she was wearing. “This is what we have to do now.”

She has volunteered as a poll worker for four years, and she said this voting site is far better run than the one at the Devil’s Den in 2016.

“It was a madhouse,” she said, chuckling.

Uncertainty looms over this election, but Young isn’t worried. She prefers to focus on helping in small ways, a lesson she has learned from her years with the Peace Corps, End Hunger in Durham, and other activist work.

“You do what you can,” she said.

At top: Poll volunteer Emma DeRose wipes down a voting booth after a voter leaves. Photo by Henry Haggart | The 9th Street journal