From the moment I wandered onto Ninth Street as a clueless Duke freshman experiencing her first days of August humidity in the Southeast, I never quite looked at the world the same way.

On Ninth Street, I worked my first service industry job where I saw, heard about, and experienced more sexual harassment than I knew existed. I fell in love with a woman and jumped into a whirl of confusion. I formed many thoughts while walking back and forth between White Star Laundromat and Bruegger’s Bagels. I cried. I laughed more.

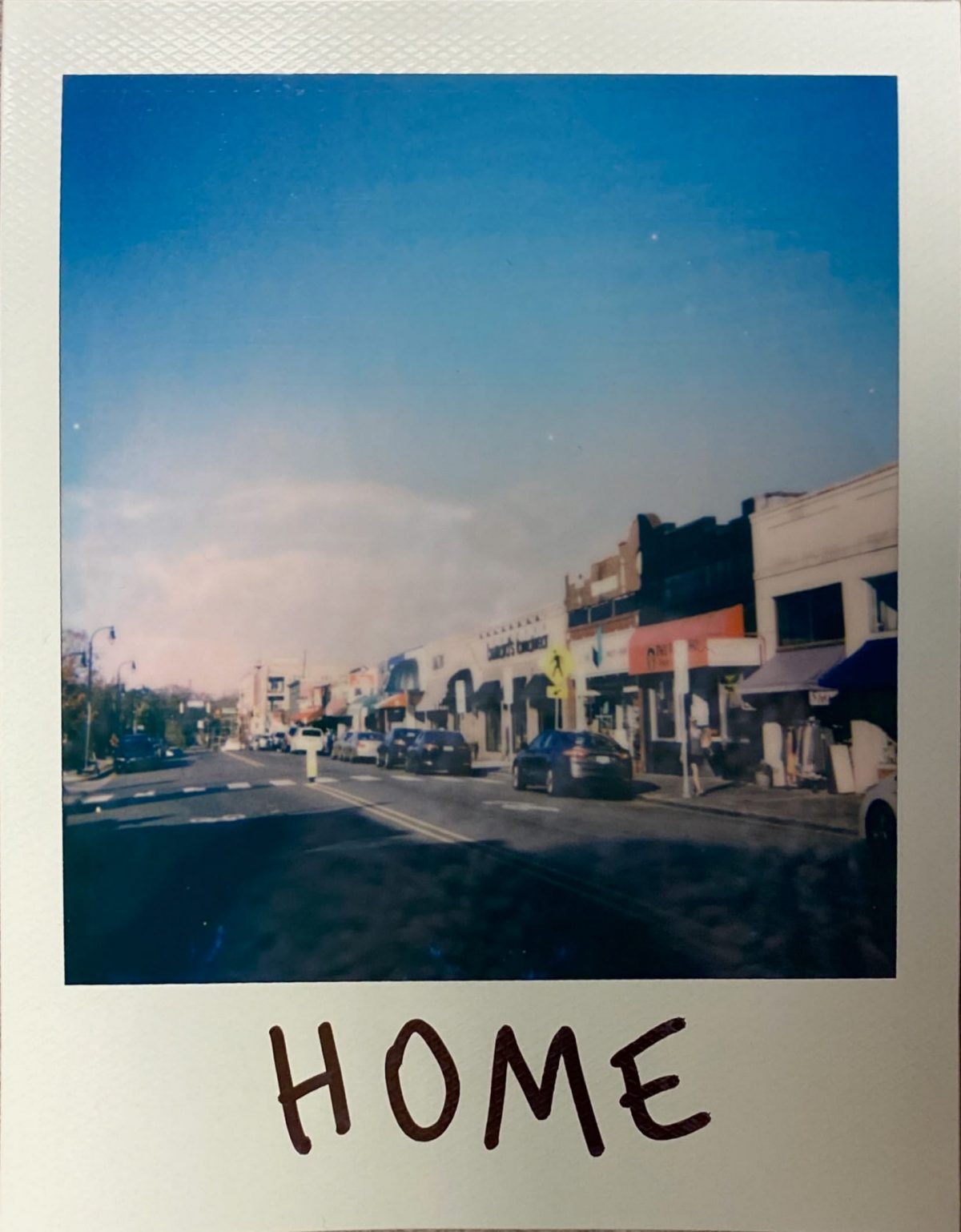

About to enter my last semester of college, I now live in Erwin Mill, a Ninth Street apartment building converted from a cotton mill in the 1970s (which I didn’t know until reporting for this story). Driving on Ninth Street a few dozen evenings ago, I was struck by the pink and purple skies gently resting on the street’s low-rise buildings and reflected, once again, on how much I love my home.

That thought came with a pang of guilt. My understanding of Ninth Street and West Durham was limited to the last four years. To truly love someone is to know someone. It was time to learn more.

Readers — this is a love story, a farewell letter, and a chronicle of my home and the people who defend it.

For decades, wheat crop covered most of what is now Old West Durham — a neighborhood that stretches north from the Durham Freeway to Englewood Avenue and west from Broad Street to Hillandale Road. Except for Pinhook, according to John Schelp, former president of the Old West Durham Neighborhood Association and West Durham’s street historian.

In the early to mid-19th century, Pinhook was a “rough and roaring” settlement whose great appeal was its tavern. After a day’s journey, travelers walking from Hillsborough to Raleigh would end up at Pinhook, which was “100 yards southwest of the southwest corner of Erwin Mill,” Schelp said.

They would kick back in the tavern, socialize with locals — including University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill students who could party at Pinhook away from authority figures — and rest up before continuing their journey the next morning.

Ninth Street itself was part of farmland owned by the Rigsbee family, whose land now holds Hillsborough Road, Carolina Avenue, 15th Street, and most of Duke West Campus. In 1892, the Duke family bought that land from the Rigsbees to build a cotton mill to diversify their investments in tobacco and expand into other industries, like textile.

The long red-brick building on Ninth Street was the first of eight Erwin Mills that the Duke family owned in the Southeast. I and many Duke students live in the first. Parizade and Local 22, both restaurants, and the 10-story Erwin Square Tower replaced the fourth, which was larger.

The development of the mill village, which stretched from Monuts on Ninth Street to the Duke Gardens, left no room for Pinhook’s ruckus, Schelp said.

“If you drank too much, not only did you lose your job, you lost your mill house… all the houses were owned by the mills,” Schelp said.

Relative to other mill villages in the Southeast in the early 20th century, life wasn’t too bad, Schelp said. Erwin Mill workers and their families had access to a health clinic, library, swimming pool, baseball field and tennis courts.

Unlike some mill villages that had company stores, Erwin Mills allowed private merchants to populate Ninth Street, Schelp said. There was a grocery store, hardware store, post office, and McDonald’s Drugstore, a pharmacy and soda shop for 80 years that served renowned milkshakes until 2003.

In the 1970s, during Erwin Mills’ slow decline, new businesses and ideas began flowing into Ninth Street. In 1974, Duke alumnus David Birkhead founded The Regulator Press, which printed political news for grassroots organizations, in the back of what is now The Regulator bookstore. A couple years later, he gathered friends — including fellow alumni Tom Campbell and Aden Field — and suggested that they rent the streetfront space and sell books, Campbell said.

Field jumped on the idea; Campbell, who had recently finished his master’s degree in environmental management at Duke and could not yet find a job, agreed to help out for a few months.

“A few months became 41 years,” Campbell said.

The Regulator Bookshop opened in 1976. Field moved on after two years and John Valentine, another Dukie, joined Campbell until they both retired almost three years ago.

The entire friend group — Campbell, Valentine, Birkhead, Field — were politically progressive. “Durham was still largely a conservative town, so we were a little different,” Campbell said.

Campbell and Valentine invited provocative authors to speak at their store, including feminist novelist Margaret Atwood, Black historian John Hope Franklin, and former Vice President Al Gore during his book tour for Earth in the Balance.

Shortly after the 1979 Greensboro Massacre, when the Ku Klux Klan and American Nazi Party killed four members of the Communist Workers Party, members dropped off copies of their newspaper on a rack at The Regulator where locals could share flyers and free information, Campbell said.

Flyers soon circulated the neighborhood, stating that there were communists on Ninth Street. “They were referring to us,” Campbell said.

Some people in Old West Durham were clearly not communists.

Don Hill’s Lock and Gun (renamed Don Hill’s Lock and Safe in 2007) on Hillsborough Road had a large cannon facing the street out front. For a while after the flyers that falsely claimed Campbell and Valentine were communists spread throughout the neighborhood, that cannon was turned towards Ninth Street, Campbell said.

“It was a little scary,” Campbell said. “This was just a few months after people who were communists got killed in Greensboro.”

By the 1980s, Ninth Street was a hub for progressives and the intellectually curious. Ninth Street Bakery, which opened in 1981 where Dain’s Place and Durham Cycles are currently, was the first bakery in town to offer organic and whole grain options, co-founder Frank Ferrell said.

Durham Mayor Steve Schewel, who helped Campbell and Field organize their bookstore the night before The Regulator’s opening, recalled often meeting other left-leaning thinkers at the Ninth Street Bakery and bouncing thoughts back and forth for hours.

While attending graduate school at Duke, Schewel worked for North Carolina Public Interest Research Group, which rented office space above what is now Wavelengths. Vaguely Reminiscent owner Carol Anderson said that “a network of lefty groups” rented offices above the hair salon back then.

Based on their interests in vintage fashion and basket weaving, Anderson and then-business partner Deb Nickell founded Vaguely Reminiscent in 1982, taking the name from folk singer Charlie King’s 1979 song “Vaguely Reminiscent of the 60s.”

Baskets and used clothes were not enough to fill a store, they soon realized, so they expanded to crafts and natural-fiber clothing. Today, that’s where you find Kamala Harris prayer candles and magnets that read “Wake Up And Smell The Complete And Utter Bullshit!” (Yes, I bought one.)

A piece of Durham history occurred in Vaguely Reminiscent. In preparation for the first official Durham pride parade in 1986, queer and progressive organizers asked then-Mayor Wib Gulley to make an anti-discrimination proclamation to protect them. Gulley did them one better and created an anti-discrimination week.

The backlash was immediate. Local religious leaders and conservatives, led by U.S. Sen. Jesse Helms’ National Congressional Club, organized a recall campaign against Gulley. Activists set up booths around Durham and sought to collect the 14,000 signatures in six weeks they needed to trigger a new mayoral election.

Anderson mobilized volunteers to visit the same places that the recall campaign was collecting signatures to tell community members why they should not sign the petition. They met on the back porch of Vaguely Reminiscent to collect the tables, chairs and informational materials they needed, Anderson said.

The recall campaign did not get enough signatures.

“There was a lot of political activism and interest in changing our community for the better,” Mayor Schewel said about Ninth Street back then. “The culture we were part of then has shaped what Durham is now.”

Like a metronome set at 100 beats per minute, time lords over places and lives, demanding that all keep up. Ninth Street is not exempt.

As national chains move into spaces on the street where local stores once thrived, Ninth Street is becoming increasingly gentrified. Construction workers are turning the parking lot across from Anderson’s store into a Chase bank, the second bank on the street. The lost lot was critical to small businesses on the east side of the street.

Anderson had planned to sell her business to a longtime employee this year. Not only has the pandemic delayed her retirement, she doesn’t know if anyone will want to take over a small business that’s a vestige of the past, perhaps vaguely reminiscent of the 80s.

“It doesn’t have the political left vibe that it did,” Anderson said of Ninth Street.

But that doesn’t mean the community hasn’t taken steps to defend itself. Between 2006 and 2008, Schelp worked with the City Council to create the Ninth Street Plan, which aimed to stave off corporate enterprise and preserve local businesses for as long as possible, he said.

The plan mandated a two-story limit on much of the east side of the street, an even split of three- and four-story buildings on the west side, and banned drive-through windows (The Wells Fargo drive-through was built before the plan.)

Fast-food chains like MacDonald’s are less likely to move in if they can’t have a drive-through, Schelp said. Knocking down a one-story unit sounds less profitable when you can only replace it with a two-story building.

Schelp and others from the neighborhood negotiated with other developers on and near Ninth Street, including Harris Teeter, the Berkshire Ninth Street apartments, Station Nine, and Duke Medical Center. They succeeded in influencing the exteriors of some buildings — lots of brick is visible on upscale apartment buildings. But no units were set aside as affordable housing with less-than market rent, as some desired.

“Money is pouring into Durham,” Schelp said. “You can either complain about the bulldozers when they show up or you can months in advance, sit down at the table, roll up your sleeves and negotiate with the developers to make something that is more acceptable to the community and the builder.”

A 1987 state law prohibited rent-control on the county or city level. While inclusionary zoning — policy requiring a given share of a new construction to be affordable for residents of moderate- to low-income — is not illegal, it is not explicitly legal either (a 2001 bill to allow mandatory inclusionary zoning died in committee).

Municipalities considering mandating inclusionary zoning worry that the Republican-held General Assembly would not only respond by suing the city, Schelp said, but also ban the affordable-housing strategy altogether.

Change is coming.

Durham City Council member Javiera Caballero said that the city is currently updating the Durham Comprehensive Plan in ways that will expand affordable housing. In coming years, the city will see a rise in multi-family homes — duplexes, triplexes, quads — to accommodate the influx of people moving to Durham and keep housing prices from skyrocketing, she anticipates.

The Comprehensive Plan will affect the entire city and supersede the Ninth Street Plan, Caballero said.

The gentrification plaguing Durham today is the inverse of 20th-century white flight, when white people moved in large numbers out of racially-mixed urban areas for the suburbs, taking wealth and jobs with them.

Affluent whites are now moving to the city, displacing long-time Black residents who cannot compete financially for a number of reasons. For one, mortgage applications for Black residents here are less likely to get approved than applications for white residents.

Although Mayor Pro Tempore Jillian Johnson could not predict the future of Ninth Street, she said that “all Durham neighborhoods are going to need to densify in the coming years in order to ensure adequate availability of housing, particularly housing that’s affordable to lower-income residents.”

So Ninth Street will change; the question is for whom? While some see rampant commercial growth (has anyone given Capital One a call?), others envision a compact and financially accessible community for all.

Since I was born, I moved back and forth between Canada, Hong Kong and Michigan. In each place, I lived with different adults. I’ve been asked countless times — which is home?

Perhaps my answer will change years from now when I settle down somewhere and start a family. But Durham is the first place that has truly felt like home.

Ninth Street today is far from the dwindling-mill-village-up-and-coming-lefty-hub where Schewel and Campbell hung out years ago. The steady march of gentrification could bury those roots.

Still, I find my story aligning and intersecting with the experiences of the mayor and the landmark bookstore founder. This street helped change how I think about politics, race, and gender too.

I also spent countless hours in The Regulator, particularly when I was desperate to escape the toxic demands of campus life. And if only you could meet all the wonderfully strange people I met here as well.

Even though I may just be another Duke student cruising through, the impact that Durham has on me and the thousands of students who wander onto Ninth Street for the first time every year far outlasts our time here.

I have wondered what this street will look like when I return to Durham as an alumna, and whether it will still hold magic like it has for me and so many before me. I don’t know, but I still have a lot of faith in the people who choose to call it home for the long haul.

All photos by 9th Street journalist Rose Wong, who can be reached at rosanna.wong@duke.edu.