Update: This story has been updated to note that Cunningham conceded on Nov. 10.

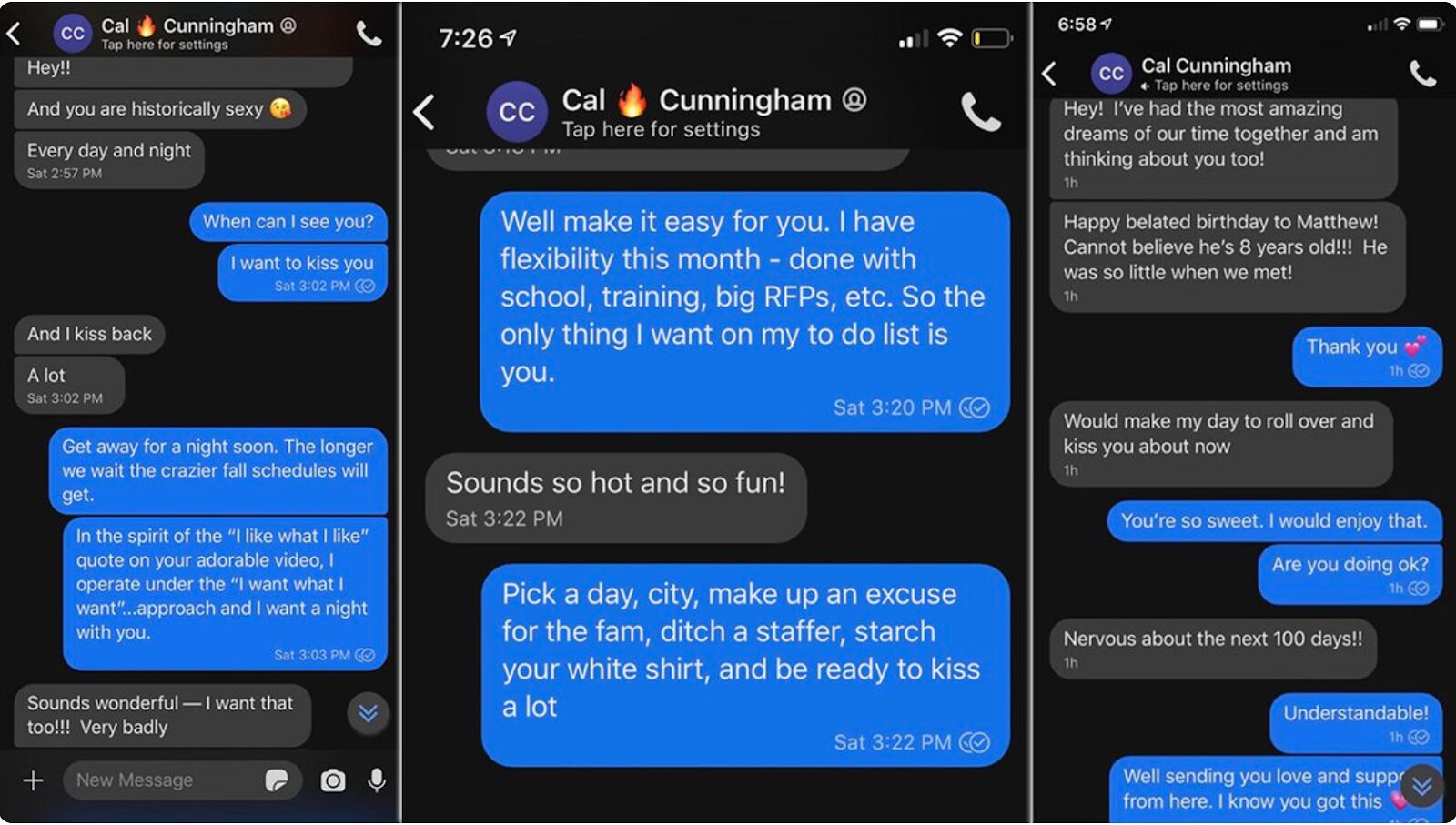

The texts were far from salacious — they sounded like messages from a nerdy college kid — but they probably cost Cal Cunningham a Senate seat.

Heading into Tuesday, most polls showed him with a single-digit edge over Republican incumbent Thom Tillis, just like they had for the entire campaign. Even Republican strategists thought Cunningham would win, said Jessica Taylor, the Senate and governors editor for The Cook Political Report.

But the messages and their ripple effect shifted the dynamic in the most expensive congressional race in U.S. history. According to the North Carolina State Board of Elections tally on Nov. 9, Tillis won 2,641,979 votes to 2,546,241 for Cunningham. The Democrat conceded on Nov. 10.

There surely were other factors that contributed to Cunningham’s defeat, including high turnout among Republicans and a boost for Tillis by Trump. And the polls that consistently showed a Cunningham lead may have been wrong all along.

Still, the biggest factor was the late-breaking scandal that zapped the Democrat’s momentum and shattered his carefully curated image.

After the conservative site NationalFile.com broke the news on Oct. 2 and The Associated Press confirmed Cunningham had an affair, his campaign went dark. The candidate cancelled events and avoided exposure to the media, leaving a vacuum quickly filled by Republican attack ads and calls from Tillis for Cunningham to come clean.

“Cunningham turned down the volume on his campaign, whereas Tillis kept it at a very high volume,” said Chris Cooper, professor of political science and public affairs at Western Carolina University. “He didn’t close very strong.”

The slow-motion strategy continued to Election Day: Cunningham dodged reporters and held limited events while Tillis crisscrossed the state.

Case in point: Cunningham visited Jackson County, and didn’t publicize his visit or alert the media, Cooper said.

“This is the middle of damn nowhere,” he said. “Cal Cunningham was across the street, and I didn’t even know it.”

The scandal also undermined the Democrat’s image as a clean-cut Army veteran who would tackle corruption in Washington. Ads about his honorable character and Bronze Star Medal felt hollow after the Army Reserve began investigating his affair.

This likely turned off some swing voters, particularly white suburban women, said Carter Wrenn, a North Carolina political consultant and columnist.

Exit polls showed Tillis fared better than expected with white college-educated women, a sign that the scandal may have hurt Cunningham with a key voting bloc.

“What was up at the end? There were swing voters, and I expect the scandal itself hurt him in the fact that it made him look phony,” Wrenn said.

“He ran as a Boy Scout, and it turned out he wasn’t one.”

Chris Kuo