At the Durham County Courthouse, judgments begin before a case is even heard.

The first judgment happens at the doors of the courthouse, where deputies decide who enters. They scan dockets for defendants’ names, wave lawyers through, and direct victims and witnesses to courtrooms. As they do so, they glance at what each person wears, determining whether an outfit is presentable for court.

The second round of judgments occurs at the doors of the courtroom. On a recent Wednesday outside of Courtroom 5A, a bailiff checks names again. This time, though, she looks closer at clothing.

She mistakes a defendant wearing a crisp navy blue suit and glossy brown loafers for an attorney. She instructs defendants whose boxers peek through sweatpants and jeans to pull their pants up. Tuck t-shirts in. Take snapback hats off. If they don’t, she warns, the judge may not hear their case.

There is no dress code in the Durham courthouse. Justice, after all, is supposed to be blind. But courtrooms are stages for human drama, where dress and decorum matter and their impact on one’s image is impossible to ignore. In other words, perception can shape justice.

“There’s a general formality in court that can be intimidating,” said Sarah Willets, spokesperson for Durham’s District Attorney’s office. “Even if no one has said to you explicitly, ‘You can’t wear this,’ you still get the sense when you walk in court that there’s a certain way things are usually done.”

In the courtroom itself, some outfits are expected. There are attorneys in suits and ties, blazers and pencil skirts. Bailiffs stand guard in beige uniforms, and the judge dons a traditional black robe.

The clothes in the gallery, however, tell a story of defendants, victims, witnesses, and relatives who put their daily routines on pause to watch judges decide fates.

* * *

When a defendant is called up, judges take their attire into account. Some judges who don’t approve of an outfit won’t hear a defendant’s case until they change, said Durham’s Chief Public Defender Dawn Baxton.

For some defendants then, an outfit can reflect the significance of the moment and indicate to the judge their regard for the legal process. On that Wednesday in Courtroom 5A — domestic violence court — the man in the crisp navy suit, Benjamin Wendt, slides a briefcase under the bench before fixing his tie. The court finds out he is representing himself.

Wendt sits next to Ananias Surratt, a young man whose clothes suggest that his court appearance coincided with his plans to go for a run. Surratt wears navy athletic shorts and a black hoodie, along with a pair of red, white, and blue New Balance sneakers.

Both men are in court for the same charge — assault on a female.

Baxton thinks judges regard inappropriate attire as disrespectful to the judicial process.

“Judges might have, in their mind, a standard,” Baxton said. They consider tank tops and shorts to be inappropriate. They take offense at some writings on t-shirts.

But for many defendants, the clothes they wear to court are the best they have. In fact, to address this issue, staff at the Public Defender’s Office have collected a closet of donated professional clothes.

“I think judges don’t take into consideration the circumstances that people are coming to court in,” Baxton said. “Some leave work and come straight to court. Others don’t own business attire. These are things that I don’t feel should be distracting a case from getting heard.”

* * *

Later that day in Courtroom 5A, a victim takes the stand. She wears a burgundy striped button-down shirt and black skinny jeans. Her large black handbag sits on the table.

Between shallow breaths, she recalls the night of July 9, one of many when the father of her children came home high and assaulted her. She fell and hit her head.

“That’s what you deserve,” she recalls him saying. Her voice cracks. She begins to cry.

Most victims and witnesses have never been to a courthouse before. In their first visit to a building consumed by decorum, they relive trauma — a judge interrogates their story, a jury questions their credibility. What they wear can affect both how they present themselves and how the judge perceives them.

“[Clothing] matters in terms of feeling comfortable and feeling like you belong there,” Michelle Cofield, deputy chief of staff at the DA’s office, said.

For years, the DA’s staff scrambled to find solutions when victims and witnesses didn’t show up in court-appropriate clothing. Legal assistants kept jackets on hand. One assistant district attorney stashed extra clothes in her office.

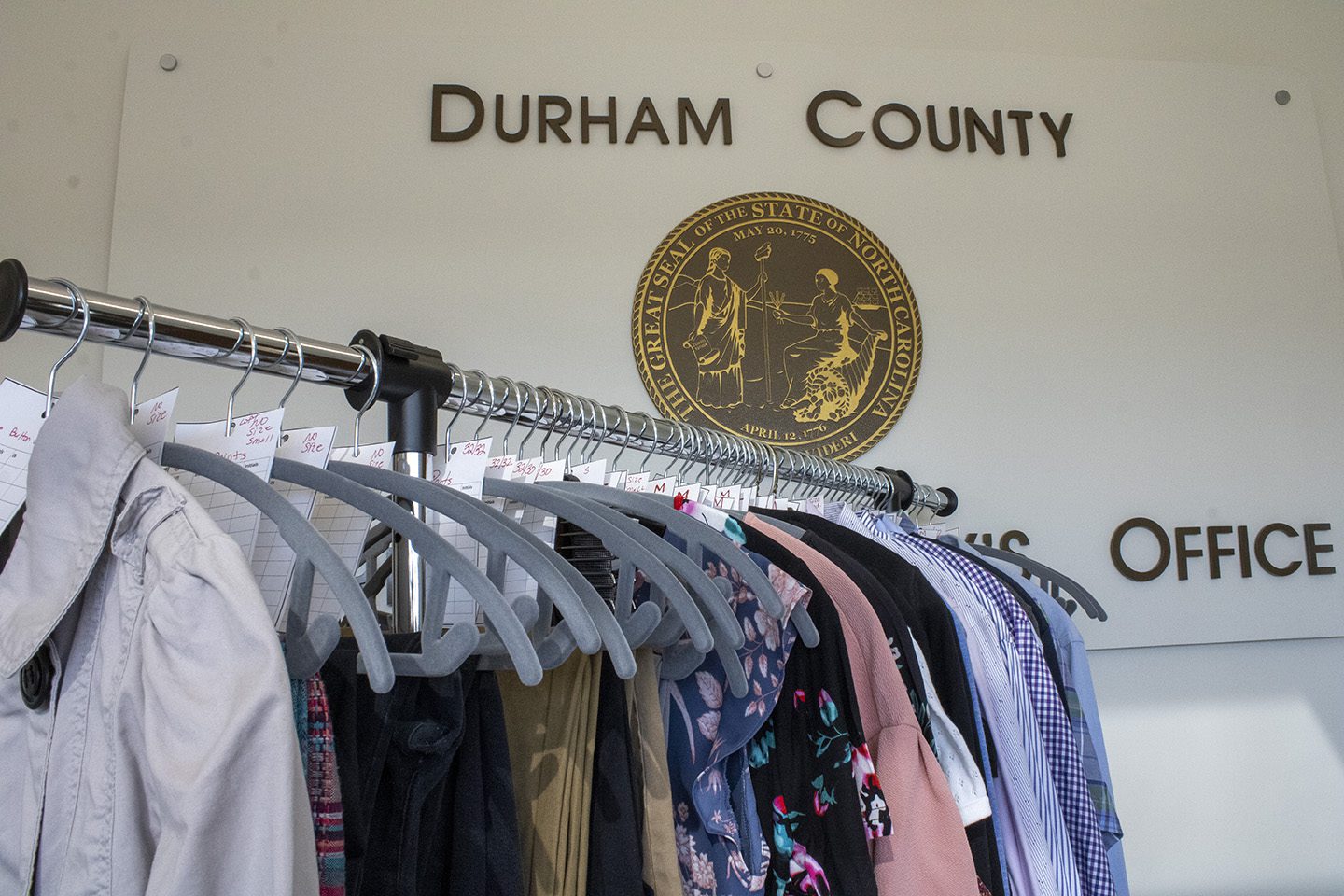

In September, the DA’s Office established a lending closet of professional attire for victims and witnesses. A month earlier, the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys allocated $500 to each prosecutorial district to purchase clothes for people to borrow. Cofield had a week to order them off Amazon.

Now, over 45 items hang on a garment rack in the corner of Room 8600, known as the guest room — a space for victims, witnesses, and their families to wait during court.

In the middle of the rack, a black dress with hot pink and turquoise flowers sits next to four identical black cardigans, size medium to 2XL. There are two short-sleeve pointelle shrugs from Loft: one in black, one in white. A salmon-colored wraparound sweater with balloon sleeves is a favorite among office staff.

“We relied heavily on sweaters,” Willets said. “It’s freezing in this building all the time.”

DA staff donated a third of the clothing. Willets points to a black button-down top with white polka dots and a cheetah motif she once wore. Her husband’s old blue dress shirt is one of 10 in the closet.

The range in clothing style and size ensures inclusivity. It also gives victims agency over a small part of the court process.

“When people are victims of crime, part of that experience is having choice taken from you,” Willets said. “Something happened to you and you didn’t have a say in it. And so we try to give people back that choice wherever we can.”

While a victim might feel comfortable in their own attire, DA staff considers how a judge or jury will view the outfit, Cofield said. Sometimes, playing a guessing game of “what people might perceive” means the DA’s office can present a more compelling case.

“We spend a lot of time working with our victims or witnesses and preparing them for court,” Cofield said. “We don’t need one other thing to get in the way.”

The goal is for the victim’s clothing to appear neutral and not distract from their testimony. If an outfit is deemed inappropriate or a wardrobe malfunction occurs, the closet is there. “Our court system is built using people,” Cofield said. “It’s not a series of automatons that are making the decisions.”

People make assumptions based on how others are dressed. It’s inescapable. Cofield searched for the right word to describe why attire plays such a big role in the courtroom, particularly for victims.

She landed on “dignity.”

PHOTO ABOVE: The Durham District Attorney’s Office provides clothes for victims and witnesses who may need appropriate attire for court. Photo by Josie Vonk, The 9th Street Journal.