Story by Sofie Buckminster; Photos by Kulsoom Rizavi

On Feb. 15, 14 union members faced the Durham Board of Education and their lawyers. The two parties took up almost every seat at the large square table — two empty chairs directly opposite each other served as a moat between them. Union pride shone bright red on one side: T-shirts, blazers, and glittery thermoses all celebrated the historic moment. In a right-to-work state, the Durham Association of Educators, or DAE, had made it to the table.

Ever since Durham Public Schools announced that it couldn’t afford the raises granted to classified workers in October, DAE has been the face of the workers’ fight for better pay. Over 1,500 new employees joined the union in the last year.

In the last two months, though, their accelerating progress hit a serious speed bump. With next year’s budget decisions looming, they are trying to maintain momentum amid all of the emotions and opinions at play in a democratic union.

“We have to be very thoughtful and considerate of how we move now,” said DAE vice president Turquoise LeJeune Parker.

***

When the school district notified classified employees on January 12 that “errors were made” and their raises were being rescinded, workers were shocked. DPS classified staff — plumbers, occupational therapists, and essentially everyone besides teachers and administrators — make as little as $3,000 per month. Anticipating a new level of income, many quit second jobs, bought new houses, or divorced spouses. The impact of revoking the raises was enormous.

The pay crisis was the result of a series of DPS errors, including misleading cost estimates from former CFO Paul LeSieur and a lack of transparency by former superintendent Pascal Mubenga once he learned the true cost of the raises. And according to N.C. State University professor of labor history David Zonderman, the DPS salary debacle didn’t come out of nowhere.

“I would argue the past 15 years have been a kind of slow-burning crisis,” he said. “Teachers’ salaries today are shockingly low in this state,” he continued, “And this one, I think, was particularly acute because really low-wage people got a raise.” And then it got taken away.

“That’s obviously a pretty egregious moment.”

The union wasted no time responding. On Jan. 31, DPS closed 12 schools after hundreds of employees called in sick for a DAE-led protest. On Feb. 5, when DAE called for another day of protest, the union organized meals — PB&J sandwiches, oranges, Gatorade, and donated pastries from 9th Street Bakery — for students to pick up in place of school lunches.

In January, February and March, crimson crowds took to the sidewalks — “Keep your feet out of the streets!” is one of DAE’s marching guidelines — to be heard. “Respect our years, respect our voice,” they yelled. “Respect our union!”

The union doesn’t encompass all affected workers — many classified workers are not DAE members — and there have been worker walkouts not staged by DAE. But, the union’s membership spans school system employees of almost every trade. And Durham is primed to support the cause, according to Zonderman.

“There’s lots of people in the community that care a lot about the public schools,” he explained. “Teachers could mobilize, I think, a fair amount of support for what they want.”

And they did. Within two weeks, the school board accepted DAE’s primary two demands: for no money to be taken back from workers, and for there to be no change to workers’ January paychecks.

In a right-to-work state like North Carolina, this degree of union action is unusual. Sanitation workers in Raleigh have been organizing strikes over the past few years, but have had trouble getting through to lawmakers, according to Zonderman. “They’ve staged various protests because they felt conditions have become so egregious,” he said, “and no one’s listening to them.”

While unions’ right to free association is protected under the First Amendment, North Carolina’s right-to-work laws prohibit closed shops, striking, and collective bargaining by public sector workers. Their employer has no obligation to meet with them and make contractual commitments about working conditions. The school system doesn’t have to listen to DAE at all.

That’s why the February 15 meeting was so important. Sitting face to face with the school board, the DAE proposed a “meet and confer” policy — basically, an agreement to meet regularly to provide union input on issues facing schools. “We can’t just meet when things go horribly wrong like this,” union member Reilly Finnegan explained.

Their pitch was compelling. The microphone bounced from person to person as union members explained how the policy is implemented elsewhere, and why they felt it was so urgently needed. DAE member Quentin Headen offered a bridge between the two sides. “It’s a team, it’s a family,” he told the board. “We would all be in it as one.”

That night, the board voted to create a group — made up of board members, DAE representatives, and non-union workers — to pursue the meet-and-confer policy. DAE called it “a historic step forward for labor rights in the South.”

Then their progress came to a crushing halt. At a Feb. 22 meeting, the school board voted against continuing to pay workers the October rates, and instead implemented an 11 percent raise over classified employees’ 2022-2023 salaries. Even though this was a raise over last year’s salary, many workers would be making less than they had in the previous six months. According to the DAE website, the “vast majority” of workers included in this change, who make less than $43,000 per year, are now taking home at least $250 less per month than in October.

For two months, DAE had gotten almost everything it wanted. Now the exhaustion was catching up to them. School board meetings continued, and the hired comptroller Kerry Crutchfield made various recommendations for next steps, but many union members found it difficult to stay engaged. “It feels very hard to see or hear any presentation right now,” Parker said. “It’s never enough.”

***

After six weeks of fighting, workers left the Feb. 22 meeting looking very solemn. Shoulders slouched beneath red shirts as union members filed out of the building, with homemade signs that were once held high hanging inches from the ground. A week ago, they’d been sitting at the table with DPS leaders. Now, they trudged to their cars next to everybody else.

Within the union, momentum stalled. Focus started to drift in different directions. Some people wanted the union to organize more days of protest, and others feared the consequences if they did.

While closing schools generates a lot of noise, it also risks alienating parents who rely on DPS for childcare and meals for their kids.

“Durham parents cannot handle last minute notices of canceled school again,” one DPS parent posted on X (formerly Twitter).

“We have to be really calculated with when we do shut down schools,” Parker said. “You have to know the lay of the land.” DAE posted “temperature check” surveys on their website to make sure they did.

Some members simply wanted action of any sort. “There’s always people who are down for whatever,” Parker laughed.

And some were ready to quit the fight. After all, it’s a right-to-work state. Even though the board agreed to pursue a meet-and-confer policy, it has no obligation to honor DAE’s opinions. “[They] could just walk away, or stop doingit, or undermine it, or whatever the heck [they] feel like doing,” Zonderman said.

But Parker doesn’t see the right-to-work laws as entirely a disadvantage. In states with collective bargaining, she says, unions often become over-reliant on the process and leave the heavy lifting to their lawyers. “They don’t have any organizing muscles,” she said.

And she’s optimistic, because DAE does. “I’m ready to fight for next year,” she said.

Meet-and-confer is only one of the union’s battle plans. They consistently milk the school board meetings for all of the airtime they can get, hosting rallies before the meetings and flooding the public comment with worker testimonies.

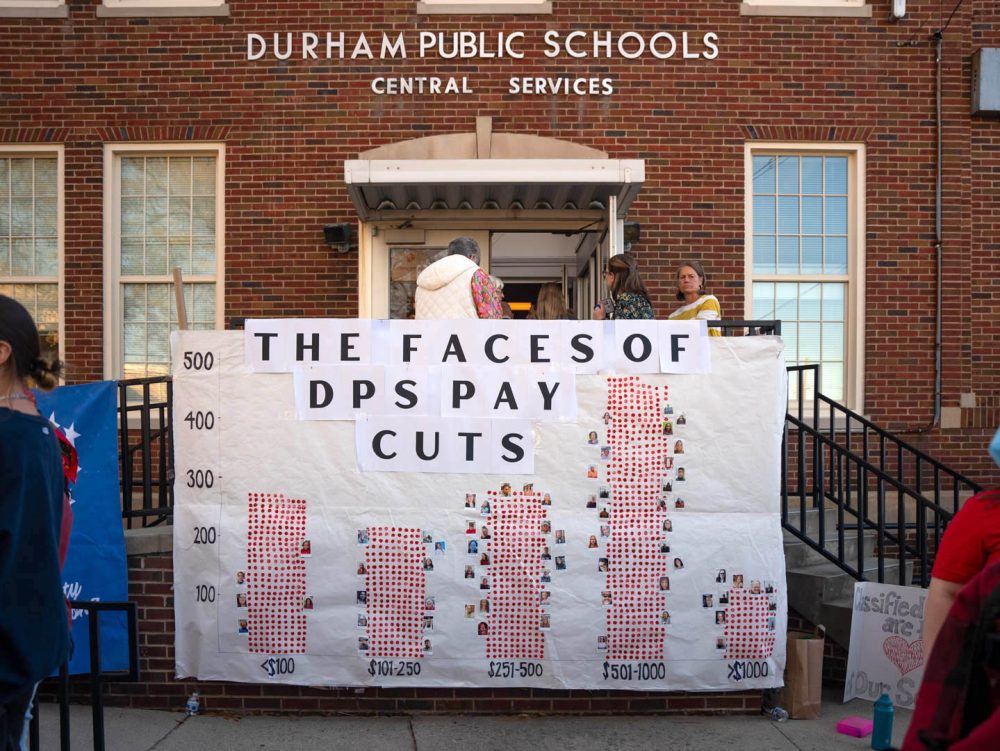

On March 21, at a rally ahead of a Board of Education meeting, they hung a massive banner covered in red dots from the entrance stairs. The dots, each representing one classified worker, were sorted into columns by how much each worker’s pay has been cut after the February decision. A woman with a Polaroid camera stood nearby, inviting people to tack their photo onto the graph in the column corresponding totheir pay group. There were 120 dots in the >$1000 column.

DAE also endorses political candidates. Schools were a top issue for many voters on Super Tuesday, when Michelle Burton, the ex-president of DAE, won a seat on the county commission — the very organization that determines funding for the school system.

“You put them in these seats,” Parker said. “That’s how you do this thing.”

As the end of the semester approaches, all eyes turn towards the budget for next year. The Board of Education has to decide how much money to request from the county commissioners, including how much classified workers will be paid.

Depending on their decision, workers could leave Durham for a more lucrative school district, says Symone Kiddoo, president of DAE. Many already have. Turnover rates were already high at the beginning of the year, Kiddoo said, and now the school system could face a “mass exodus.”

“If you couple the real material needs of, ‘I can’t afford to work here,’ and ‘I feel like my employer doesn’t care about me,’” Kiddoo said, “People will find another place to work.”

This is exactly what DAE is trying to prevent. The union has drafted its own budget proposal for next year. It insists that the school board request $18.3 million to cover worker compensation — enough to restore the October pay rates in full.

“Our budget vision is ambitious, but it has to be,” Parker said. “We can’t afford to bleed anymore.”

***

Editor’s note: The school board is expected to vote on next year’s budget at its meeting on April 25.

Above: DAE members rally on Jan. 31. Photo by Kulsoom Rizavi — The 9th Street Journal

Sofie Buckminster