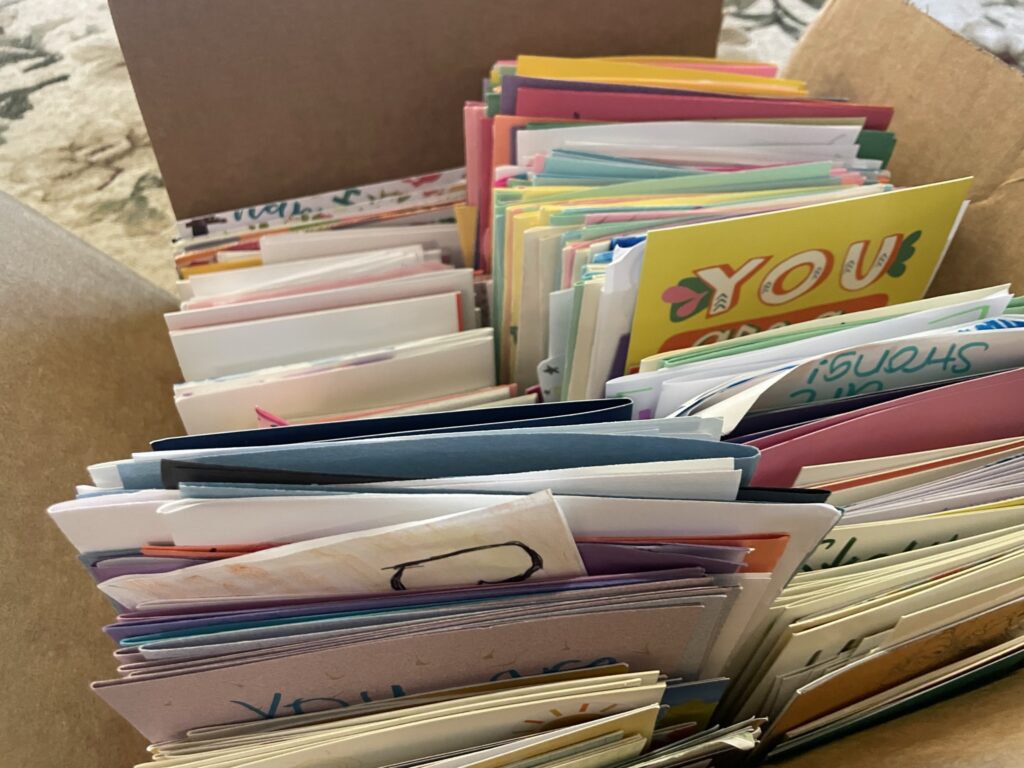

In every corner of the room—on the bookshelf, on the piano, under the bench—are boxes stuffed with hundreds of cards of every size and color. Amy Steeves, a short, smiling 36-year-old woman, looks right at home. “Welcome to Amy’s Rays of Sunshine headquarters, also known as my living room,” she laughs.

She has a quote tattooed on her arm: “Keep your face towards the sunshine and the shadows will fall behind you.” It’s what got her through cancer treatment and the motto of her nonprofit organization, Amy’s Rays of Sunshine.

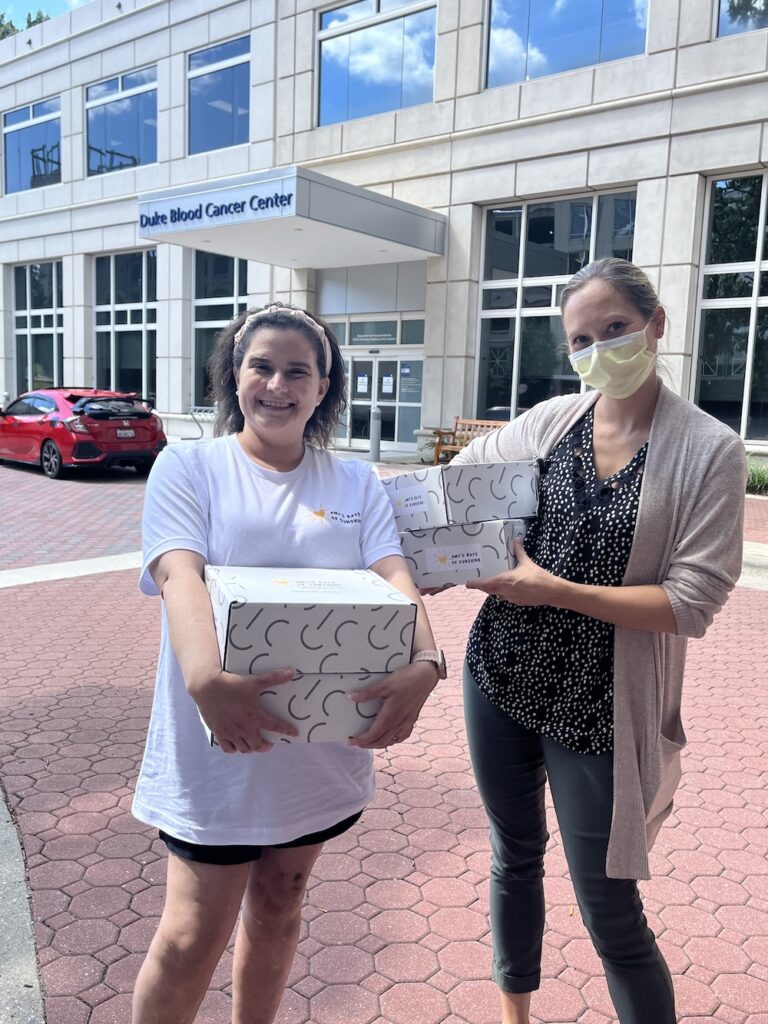

Founded in 2020, Amy’s Rays of Sunshine grew out of Steeves’ own cancer experience, which landed her at the Duke Blood Cancer Center in 2019. The project began as Steeves’ effort to support patients in that ward undergoing an isolating experience like the one she went through.

The organization, based at Steeves’ home in Apex, sends boxes of cards, handwritten by volunteers, to patients undergoing bone marrow transplants at local hospitals and to hospitals across the country, giving patients hope and encouragement through the kindness of strangers.

Steeves was 27; she was in a different phase of life from other patients in the ward and the only one with young children at home. “It was very much, don’t look at these statistics, none of them apply to you. Like, we’re kind of in uncharted territory,” she says. “Most days in the unit, I was the only one under 60.”

At first, the lymphoma responded to chemotherapy. But after three years in remission and the birth of her second son, Steeves’ lymphoma returned, and she needed a bone marrow transplant. There was no match for her on the match registry, so she did a transplant with her own stem cells and was isolated for 30 days.

Six months later, the lymphoma returned. This time, doctors found a perfect match, and in March 2019, Steeves had her second transplant. Once again, she was isolated—away from her husband and two young kids, ages 5 and 18 months—this time for 90 days.

That’s when the directors at her older son’s preschool stepped in, setting up a card drive in the lobby of Apex United Methodist Preschool. At the beginning of her 90 days of isolation, they sent her a box of 90 cards: one to open each day.

The transplant was successful, and Steeves has now been cancer-free for four years. When she got home, she put the box of cards in her dresser as a reminder of what she’d been through. “I would just look at it all the time and think, ‘I have the most incredible support system … I wish everybody could have a box of sunshine like that.’”

Starting a nonprofit was overwhelming. She posted on Facebook asking for advice and Googled how to make a website. A former colleague’s husband, a law professor, helped her file all the paperwork to get started. She found people to help her with social media (“I didn’t know what a reel was!”) and soon her team grew to nine people.

One of those team members was Lauren Cessna, a friend of Steeves’ from pharmacy school, who helped with social media and general consulting. Cessna has also benefited from the cards herself. Cessna, who had a one-year-old at home, was diagnosed with lymphoma shortly after Steeves. About a year ago, when Cessna relapsed and needed a second bone marrow transplant, she found herself on the receiving end of a box of cards.

“Amy was like, ‘We’re gonna send you the best box ever!’” she laughs. “It was amazing to see how supportive complete strangers could be.”

Amy’s Rays of Sunshine was launched in March 2020. Within a few months, hundreds of cards were coming in from people excited about the organization. “I was so naive that I really thought cards would just trickle in, so I put my home address when I started it,” Steeves says. “And then I would come home and there’d be like 300 cards on my front porch.” (She now has a post office box.)

The organization targets young adults ages 18-50. “There are so many resources for the kids’ units,” she says. “When you’re a young adult, you’re just kind of trapped in the middle.”

Hayley Olsavsky, a recreational therapist who distributes boxes at the University of North Carolina Hospitals in Chapel Hill, likes that the boxes take attention away from diagnoses and put it back on patients. “They’re so much more than just what they’re going through at the time, and have so much more to look forward to,” she says. “The package is almost like being connected to someone who’s gone through it.”

Having someone local also means a lot to patients, says Olsavsky: not only has Steeves gone through what they’re going through, but she did it just 20 minutes away.

Nowhere is Steeves’ impact more personal than at Duke. Bethany Henshall, a clinical social worker who distributes boxes at the Duke Blood Cancer Center, originally knew Steeves as a patient undergoing treatment. “I’ve seen her through her journey and stayed in touch with her, so when she shared that she wanted to give back to other patients who were going through what she had gone through, I was excited to help her.”

“Amy is an inspiration because she’s been through so much … I just don’t have the words,” she says. “I’m so happy that things are going well for her and that this program is available to our patients.”

On their first day of treatment, patients get a birthday card with a letter from Steeves. “That makes it way more special,” says Henshall. “The patients feel like, ‘Ok, this person gets it.’” In addition to the cards, the boxes are filled with donated coloring books, chapsticks, lotions, and pens with explicit phrases, selected from the organization’s Amazon wish list.

The organization’s website includes guidelines for writing cards: nothing religion- or gender-specific, stay encouraging rather than focusing on the disease. Steeves takes 10 minutes every night to go through cards and reads every one. “I don’t hesitate to throw cards away,” she says. “I’ve thrown away cards that are like, ‘God gives His toughest battles to his strongest soldiers.’ … Some of the more meaningful cards are when people are just acknowledging, like, what you’re going through totally sucks right now. And I’m thinking about you and I hope tomorrow is better than today or today’s better than the day before.”

Many of the cards are written by kids as part of school card drives, and many of the boxes are decorated by preschoolers, with a few noticeably better drawings courtesy of their teachers.

“A lot of the kids’ cards are written backward, like they don’t know how cards work,” she laughs. Sometimes kids forget to include the answers to their jokes—so Steeves and her son Google the answer and write it in the card.

Steeves’ kids like to dictate their jokes for Steeves to write on cards—jokes like, “‘Why did the chicken cross the road? Because this friend was over there,’” Steeves says. “So I write it, and then I’ll write, ‘May you have the confidence of a five-year-old telling this joke.’” Her kids also decorate boxes and help sort cards.

“I don’t think my kids are old enough to truly understand the impact. And I kind of want to shield them from how hard it really is,” she says. “But they understand that these cards are going to people that are in the hospital and don’t feel good, so let’s write them a joke, and they’ll laugh.”

For Steeves, life post-cancer looks very different from life pre-cancer. “Cancer shows you what’s important, and what to spend your time and energy on,” she says. After she got sick, she quit her job as a pharmacist and decided to “just do things that make me happy.” She recently started working part-time at the same preschool that organized her card box four years ago, where her younger son is now enrolled.

“We had a card drive at our staff meeting the other month for Amy’s Rays of Sunshine,” she says. “People who wrote cards for me when I was sick are now helping me spread sunshine and our mission to others. So it’s come full circle.”

Steeves sits on her living room floor, going through carefully sorted cards. She holds up one that reads, “You are a miracul, an awesome miracul.”

“See?” she says. “Like, how would this not brighten your day?”

Some people include letters to Steeves with their donated cards, telling her of their own cancer experiences or how inspiring her mission is. She keeps them all.

Even though Steeves loves her work, she has still needed to create emotional boundaries.

“If I really start thinking about it—if Duke wants 10 boxes, that means there’s 10 people going through this crap. And they’re young, and they probably have kids, and it’s so unfair …” But with time, she’s shifted her mindset. “I can’t change what’s happened to these people. And I don’t have any power over what happens to them in the future. But I can bring them a little bit of sunshine, and hopefully, for these next 90 days, make them smile at least once a day. And that’s more than I was doing before.”

“I wish I had a normal life. I say that all the time—I would trade anything for just a boring normal life,” she says. “But I’ve been given this messy, crazy one. And so at least I get to do something with it now, you know?”

Above: Amy Steeves with her boxes of cards for cancer patients. Photos by Elise Hammond — The 9th Street Journal

Elise Hammond