It’s Saturday night at the Durham Bulls Athletic Park, and as fans make their way to their seats and raindrops begin falling from the night sky, Chris Ivy opens a secret door behind left field.

The door is hidden from view by a pretzel stand. Ivy walks through a dingy corridor behind a giant video board, passing the fog machine that blows steam through the nose of the mechanical bull above.

“It’s like a cave!” he exclaims, as water sprinkles in from the ceiling.

As Ivy rounds the corner, a hideout comes into view. A long wooden porch sits against the outfield wall, about 10 feet above the field and just below two rows of seemingly boarded-up windows. The porch is littered with more boards, each displaying a white number on a dark green background, poised for the chance to make it on the wall.

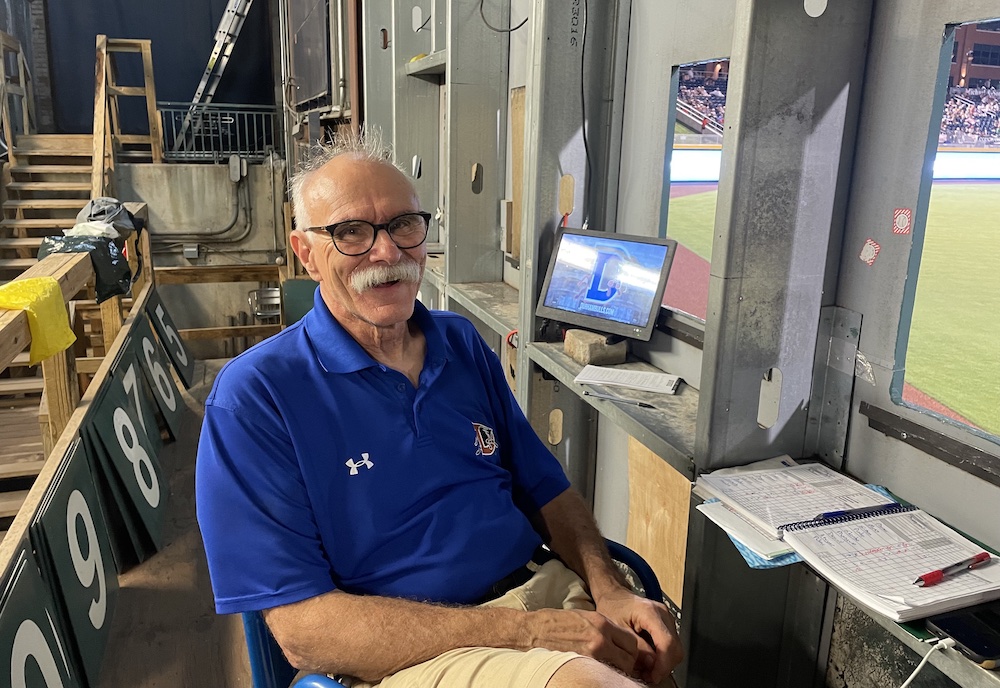

Ivy, 75, has worked here for the past 17 seasons. He is the man behind the Bulls’ manually operated scoreboard.

Manual scoreboards are a rarity these days. They appear in only three of the nation’s 30 AAA-level parks, including the one in Durham. The most famous manual scoreboards, in Boston’s Fenway Park and Chicago’s Wrigley Field, were built in the 1910s. Unlike most modern franchises, the Bulls did not opt for the digital alternative when building the DBAP in 1995.

“It’s a link to the past,” Ivy says about the analog version. “For the purists, it’s nice to have a link to the old stuff.”

The only column immediately identifiable from behind is the wide one to Ivy’s far right. A stack of enormous boards with names of visiting teams sits below this wide opening. Fortunately, someone has already hauled the “NORFOLK” board into place at Ivy’s request. His experience has earned him a few privileges.

Ivy climbs the wooden stairs up to the porch and begins preparations for the game, where the Bulls will take on the Norfolk Tides. He arranges the green placards numbering 0 through 20 — each the size of a human torso — and stacks them by group on his platform. The 0’s are most plentiful; there are 22 in total, a testament to the low-scoring nature of baseball.

“I sit in the ninth inning,” he says casually.

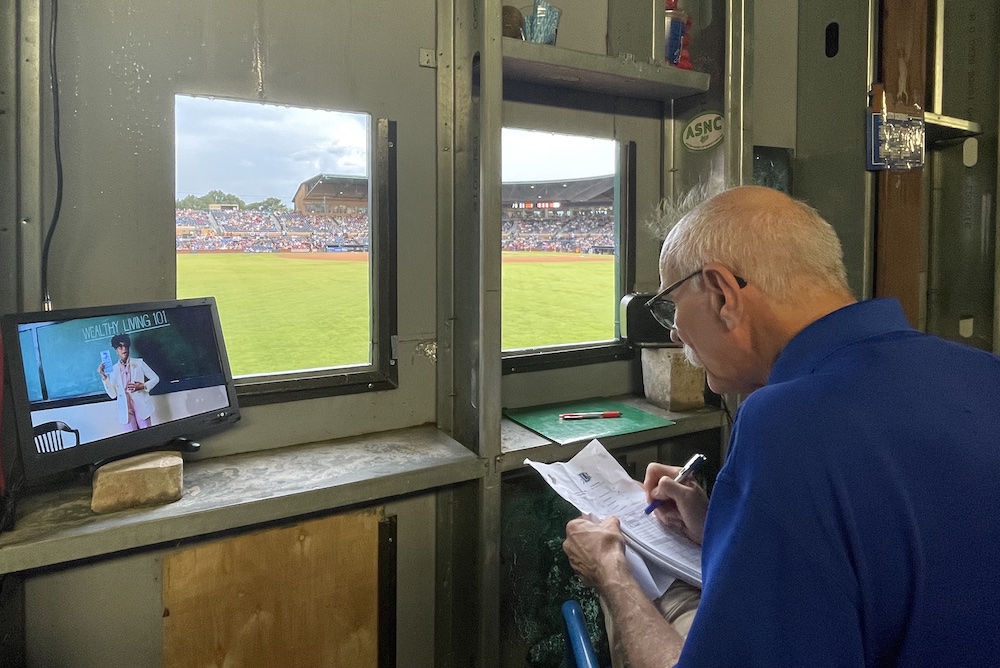

Answering my confused look, he slides a board from a slot on the scoreboard wall, revealing his window for the night, overlooking the field. Fans who glance up at the scoreboard may notice a gap under the number “9,” representing the game’s ninth inning. That hole in the scoreboard is where Ivy watches the game. He pulls up a chair and invites me to remove the adjacent board and “sit in the tenth.”

The view from our makeshift windows is immaculate. Bulls players warm up just feet away in the outfield grass, and the grandstand behind home plate stands out against the pale blue sky and setting sun. A strong breeze blows towards us; the night’s fly balls have a good chance of becoming home runs.

Ivy’s nook behind the outfield lacks air conditioning, so he places a box fan next to his seat. He pulls out a transistor radio to hear the live broadcast.

Ivy has lived in Durham since 1980, the same year the Bulls returned to the city. After a career in social work and decades of cheering for the team, he decided to apply for the scoreboard operator job when it opened in 2008.

“I don’t know if anybody else applied,” he says. “I used to tease the guy who gave me the job. I said, ‘Nobody else applied, because people either think you’re the best job in the world or you’re not.’”

Regardless of how he got the job, Ivy is thankful for it.

“It’s really fun to be this close to all the action and have a role in it,” he says.

Just then, the Tides’ leadoff batter hits a missile in our direction. The ball smashes off the wall like a gunshot, and Ivy gets to work. He grabs a “1” and makes his way left to the column labeled “H” for hits. He slides out the “0” from the top slot and inserts a “1” to record the hit.

In the bottom half of the inning, Austin Shenton of the Bulls hits one so hard that we never hear a bang. It sails overhead for a grand slam. Now Ivy’s tasks start to pile up.

“When you’ve got bases loaded and then a single, you’ve got to change the runs and the hits. And then you gotta change the run total for the inning. And before you can do that they may hit a double, and there’s two more runs in.”

In addition to his radio, Ivy has a small television broadcasting the game. The TV broadcast lags a few seconds behind the game, so he uses it to catch up if he misses anything.

“Last week they hit a ball, and when the outfielder jumped, his glove came through my window. The television went flying, but the antenna line kept the TV hanging so it never hit the ground.”

Ivy keeps his distance from the scoreboard window on fly balls, but always stays close to the fan. The humidity in the “cave” is starting to settle in.

“I’ll oftentimes invite a parent and a kid to come back here,” he says. “Either they think I’m crazy, or they think it’s unbelievable. But I like numbers, and I like keeping score, and when I’m out here, it’s sort of like a Zen thing for me.”

With four home runs already there’s no time for meditation tonight, however. By the end of the sixth inning, the Bulls have six hits and lead the Tides 6-5. Ivy’s stack of sixes is getting a little thin.

In between the action, Ivy shares anecdotes about baseball celebrities: he used to chat with Cleveland Guardians manager Stephen Vogt when he played left field for the Bulls; his mother once dated legendary Yankees pitcher Whitey Ford; his wife saw actress Susan Sarandon at a local park during the filming of “Bull Durham.”

Ivy seems to have a following of his own in the local baseball world. Fans who have joined him behind the scoreboard often ask to return. He gets one such request tonight, communicated via text by the operator of the pretzel stand outside. Samantha Wynn, in addition to serving soft pretzels, serves as a filter for Ivy’s many visitors. He turns tonight’s would-be guest away on account of his current companion.

Later, he gets another text; his friend just saw him on television. Sure enough, Ivy’s TV flashes the manual scoreboard, and his white mustache is visible in the ninth-inning window.

Another home run from Shenton and a grand slam by Cameron Misner put the Bulls up for good. By the time the ninth inning begins, the Bulls are firmly leading 14-5 and Ivy has gotten plenty of steps in for the evening.

Bulls reliever Manuel Rodríguez gets a groundout to end the game, and the crowd cheers. The win gives the Bulls a series victory over Norfolk and rewards the fans for sticking it out in the rain.

Ivy fetches a “0” — the Tides’ ninth inning run total — and brings the placard to the window he’s been peering through all night. He slides the board into the remaining empty frame, completing the scoreboard and closing the shades to his hideout.

After the team’s earlier offensive explosion, fireworks seem almost redundant. Nevertheless, we exit the cave to see the Bulls’ Saturday night firework show. The rain has stopped, and as fireworks light up the ballpark, fans marvel at the sight.

But it’s the view framed by a cutout in the scoreboard fence that Ivy comes back for again and again. Come next game, he’ll be back in his hideout behind the scoreboard, dodging fly balls, sliding placards into place, and watching the game from his unique perch. And he just might let one of tonight’s fans join him.

Pictured above: Chris Ivy has manned the Bulls’ scoreboard since 2008. Photos by Travis Swafford — The 9th Street Journal

Travis Swafford