The Greensboro sit-in of 1960 is famous, celebrated in museums and history books. Yet three years earlier, a group of seven young activists sparked the sit-in movement by refusing to leave a segregated ice cream parlor in Durham on June 23, 1957.

As the 65th anniversary of the Royal Ice Cream sit-in approaches next week, Mary Clyburn-Hooks, one of two surviving members of the “Royal Seven,” reflected on her part in a critical episode of the Civil Rights movement. Hooks, now 85, recounted her story in a phone interview from her home in New Jersey.

In 1957, she was living at the Harriet Tubman YWCA in Durham, which also provided housing for Black student nurses. Hooks soon befriended fellow residents Vivian Jones and Virginia Williams.

As the trio left the building one Sunday, they were intercepted by a group of activists. The group was led by the Rev. Douglas Moore, a classmate and contemporary of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Hooks, Jones, and Williams were invited to a private political gathering.

“These men were getting ready, Reverend Moore and other guys,” Hooks said. “And so, they were saying that they were getting ready to go to [Royal Ice Cream Parlor] and did we want to ride with them. And that’s how we got to meet them. That’s how we got there.”

Located at the corner of Dowd and Roxboro streets, the Royal Ice Cream Parlor was popular with the Black community. Yet the business forced its Black patrons to enter through the back door and eat at separate tables.

“To me, they had moved in our neighborhood and I couldn’t understand why they wouldn’t treat us better than that, than not letting us sit down,” Hooks said.

Following an evening church service led by Moore, she and her partners went to the ice cream parlor and sat at a booth reserved for white patrons. She remembers ordering “top-shelf stuff”: a generous serving of ice cream with chocolate.

To take up seats in booths reserved for white customers was to defy not only city ordinances but social conventions of the Jim Crow South.

“They told [Moore] that if we were to get waited on, we would have to go on the colored side,” Hooks said. “But for some reason, we told them we didn’t want to go there. And there were some white people in there when we first went in. But after we sat down, they jumped up and ran out of the place and I saw them peeping back in there, I guess to see what we would go and do.”

A busboy asked the activists to leave the booth. When they stood their ground, the manager, Louis Coletta, called the police. The Royal Seven were arrested on counts of trespassing and were fined $10 each plus court costs the next day.

They appealed their case to Durham County Superior Court, but an all-white jury upheld the guilty verdict after just 24 minutes of deliberations. The North Carolina Supreme Court also heard their case and maintained the legality of segregated facilities. Despite another appeal, the protesters were denied a trial at the national level.

The community’s reception of the sit-in was mixed. Some believed that Moore’s actions were too risky and radical, especially at a time when the local NAACP was still fighting to dismantle segregation in public schools. More conservative civil rights activists feared that the losses in the courts set a dangerous legal precedent.

“I was shocked, because a lot of colored people thought it was terrible,” said Hooks.

Though the Royal Ice Cream sit-in did not bring about the end of legal segregation in Durham, it reignited the conversation about civil rights locally and inspired area youth to follow the Royal Seven’s example. Protests organized by Moore and prominent Black attorney Floyd McKissick sprung up in and around the city. In 1963, after six long years of picketing and protests, Royal Ice Cream Parlor was finally integrated.

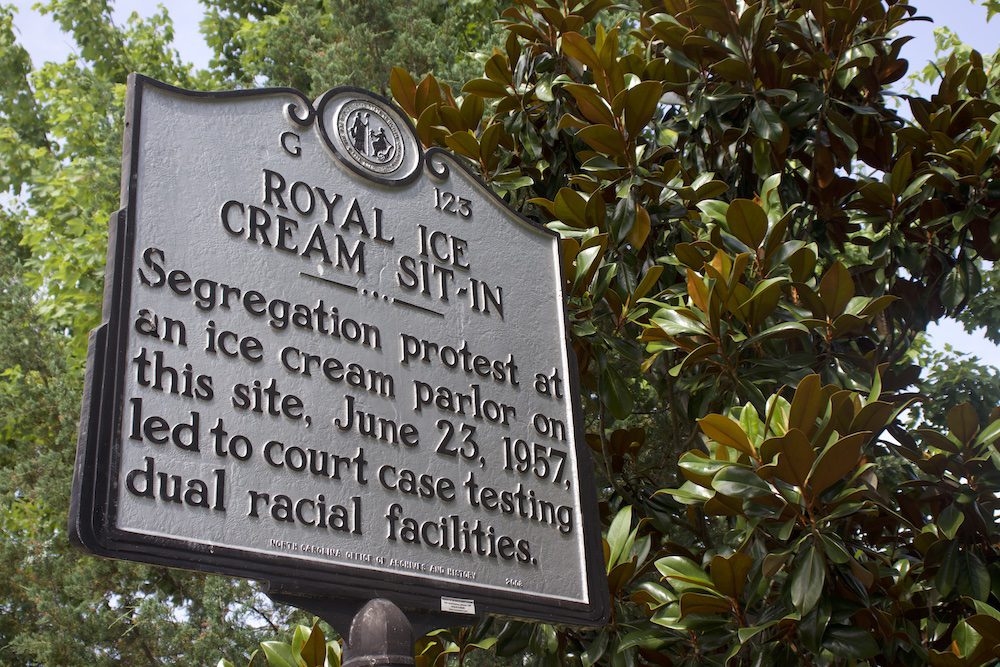

The North Carolina Office of Archives and History placed a historical marker at the site of the parlor in 2008, which states that the sit-in “led to court case testing dual racial facilities.” The seven are also commemorated in vivid color as part of the Durham Civil Rights Mural, located at 120 Morris Street.

Hooks has never taken her rights for granted. “Every time I get a chance, I try to sit down somewhere,” she said.

Though the story of the sit-in may not be widely known, it remains an important part of civil rights history in the South. As Hooks said, “It got started in Durham.”

Above (from left): The Rev. Douglas Moore, Mary Clyburn-Hooks and others pray before entering the Royal Ice Cream Parlor in 1957. Photo courtesy of the Durham County Library’s North Carolina Collection. Center: A historic marker commemorates the Royal Ice Cream sit-in. Photo by Maddie Wray — The 9th Street Journal

Sevana Wenn