“You guys ready to watch paint dry?” asks Julius Richards, an election services manager, as he walks through the winding hallways of the Durham County Board of Elections building.

Susan Pochapsky, a self-described “boomer” and a volunteer for the Durham Democrats’ elections team, laughs and disagrees as we arrive at the room where the election equipment will be tested.

“I enjoy the nitty-gritty. If I had been a young person, I probably would have ended up working here.”

Pochapsky is on hand for day one of the Logic and Accuracy Testing event on Wednesday. The annual pre-election event aims to ensure that the machines used to tabulate votes in Durham County are providing accurate results.

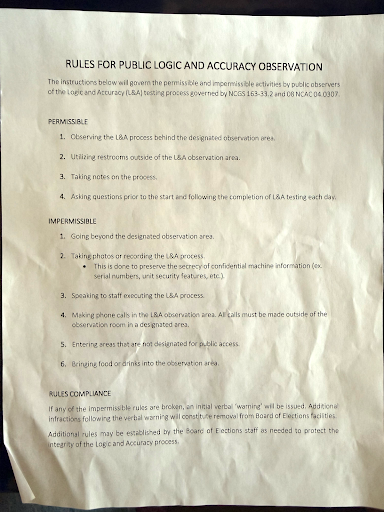

In the room, a stanchion separates a row of folding chairs from the testing area. A rules sheet for observers is carefully placed in the center of each folding chair indicating what is permissible and impermissible. The event is open to the public, but visitors must register in advance, check in at the front desk, and wait in the lobby until the event officially begins to be escorted back by a staff member.

Permissible? Observing the “L&A process” from behind the designated observation area, utilizing restrooms, taking notes, and asking questions (but only prior to the start and following the completion of the testing each day).

Impermissible? Going beyond the designated observation area, recording or taking any photos or video, speaking to staff, making phone calls, or bringing in any food or drinks.

For all the security measures, there are only two observers. Me, and Pochapsky.

“I’m such a nerd, I’m an election groupie,” she says with excitement as we take our seats. Pochapsky, dressed in navy yoga pants and a green fleece sweater, her gray hair pulled back in a ponytail with a black velvet scrunchie, seems right at home as she pulls out her notepad.

On the other side of the barrier, akin to one separating lines at airport security, three green cushioned swivel chairs sit on each side of a long white plastic table. Six staffers start to set up their stations, where they will be until 5 p.m. that day, and again from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. for at least three more days, until all machines have been tested.

“Yeah, this is really precise and intricate stuff,” Pochapsky says. She certainly isn’t lying. During the testing, she scribbles notes on her notepad explaining the varieties in election machines — from the DS 950 fast scanner to the DS 200 tabloiders, which take between 20 and 30 minutes to test. In Durham’s upcoming March 3 election, there are 36 unique ballot styles tailored for each voter depending on their voting district and political party.

The lack of other observers does not dull her spirit as she closely watches the proceedings. She arrived at 9:45 a.m. and plans to remain until 1 or 1:30 p.m.

Pochapsky has been consistently monitoring activity by the Board of Elections since 2016, she explains.

She was an actor, director, and playwright by trade, working on everything from voiceovers in commercials to producing children’s theater and starring in movies. But in 2004, she moved to Durham to be with her husband, David Ball.

“Acting is such an obsession thing. You are just busy all the time. If you’re not busy, you’re trying to get busy,” she said.

And now Pochapsky has a new obsession. Elections.

She enjoys political volunteer work centered on service as opposed to individual candidates’ campaigns, and helping to “give folks what they need to vote and get their votes counted.”

Pochapsky attends public functions for Durham’s Board of Elections and the North Carolina State Board of Elections as part of a team of volunteers with the Durham Democrats. In addition to the L&A testing, those include board meetings, ballot recounts, hearings, and vote challenges. Her goal is in part to inform two newsletters she writes for the Durham Democrats, one with election information updates and one for the 75 Democratic precinct chairs around the county.

“I try not to drag casual readers into the weeds of election law and lore where I myself like to wander.”

Pochapsky also attends these events to be a witness; to be able to testify on behalf of the Board of Elections in any court proceedings.

“Election boards are being attacked; it can happen to any of them at any time; and if the attack is baseless I’ll be there to say so.”

A third goal she describes as her own “peculiarity:” to immerse herself in the intricacies of the election process.

“It’s as mad as, say, learning watch-making or making models of ships that can slide into bottles. (Fun fact: Abraham Lincoln, early in his political career at least, believed that recent immigrants should be allowed to vote in local elections.)”

There’s a quiet stillness in the room aside from Pochapsky’s pen scratching. Otherwise the beeps, buzzes, and hums of the machines are broken only by occasional chatter from the staff.

With a winter storm predicted for the weekend, they reminisce on the last big storm in Durham.

“It was when I was in elementary school,” Richards says.

“So five years ago?” another staffer jokes.

Pochapsky mutters that she and her husband call Durham storms “dandruff,” nothing compared to what they saw living in the Midwest.

At 10:31 a.m., Pochapsky suggests that I observe the full process of validating a machine.

“That’s when you’ll really get the good stuff,” she says.

And so I watch as an older, white-haired man begins the process. Wearing a gray vest with the Durham County Board of Elections logo on it, he pulls out his checklist. He unzips a bag of equipment, unraveling cords and headphones. After sanitizing the machine’s screen, he plugs in a memory card, turns on the machine, and inserts a ballot. (It’s a sample ballot, Pochapsky tells me.) When the machine spits it out, he feeds the ballot back in, pausing to take a sip from his green water bottle.

The gray vest indicates that he’s an unaffiliated voter, Pochapsky explains. Among the six staff members working, there are four gray vests, one blue, and one red.

The lone blue vest belongs to Richards.

“He’s a machine whisperer,” Pochapsky says to me, shaking her head in awe.

Clearly, Pochapsky isn’t the only one with this sense of awe. In one hour in the Logic and Accuracy testing room, the other staffers have many questions for Richards.

“You have to test for a marked ballot in every style?” one staffer asks.

Richards responds with a nod.

One younger man (a “newbie,” according to Pochapsky) mentions to Richards that the styluses keep coming undone.

Pochapsky sighs knowingly. “The velcro from the pens come loose all the time. They really should be replaced.”

At 11:03 a.m., the testing process is done. The staffer puts the last check mark on his checklist. He puts the equipment back into the bag and places it on a shelf.

He’s finished — but just with one machine. The Board of Elections tests 157 machines before every election. And so, the staffer gets another bag of equipment from the shelf on the left-hand side of the room. Returning to his desk, he starts anew: opens the bag, unwraps the cords, and powers on the next machine.

fiona shuldiner