In 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested in Alabama for refusing to give her bus seat to a white passenger. More than 10 years earlier, Private Booker T. Spicely, a Black soldier stationed in North Carolina, was fatally shot by a Durham bus driver when he objected to segregated bus seating.

Parks is a household name, but Spicely’s story has seemingly faded into oblivion. That may soon change.

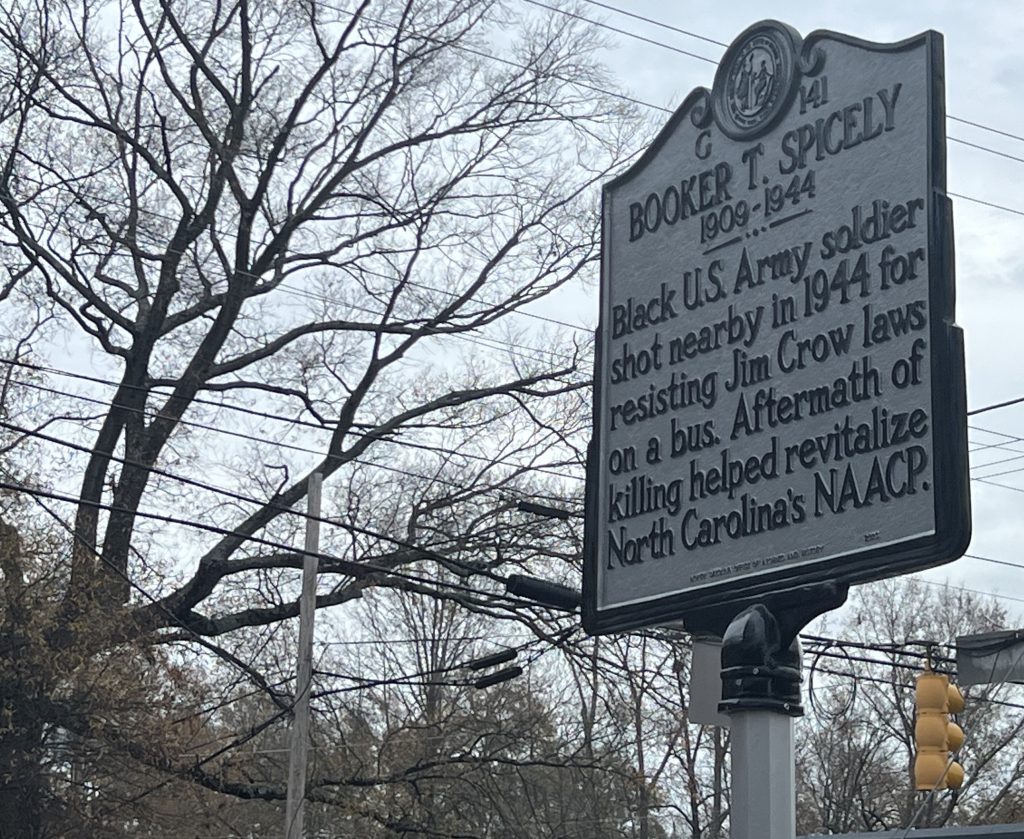

On Friday, more than 200 Durham community members gathered on the corner of West Club Boulevard and Broad Street to witness the unveiling of North Carolina’s newest historical marker in honor of Spicely’s death — the only one in the state that makes explicit reference to Jim Crow laws.

The event took place on what would have been Spicely’s 114th birthday, just a few blocks away from the site where he was shot and killed. In attendance were mayor-elect Leonardo Williams and 20 members of Spicely’s family.

“[Highway markers] are designed to spark interest, to get people to look deeper, to research, to find out what exactly happened and why this is important, whether it’s a person or an event,” said Reid Wilson, the secretary of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, while addressing the crowd.

“It’s to highlight lesser-known aspects of our history,” he added.

***

The ceremony began with a prayer. Members of the crowd hung their heads in solemn devotion, unfazed by the groaning of car engines or the screeching of a school bus coming to a halt.

The unveiling drew an eclectic mix of Durhamites. Some carried their bicycles and dogs in tow. Most wore casual fall attire, but a few audience members donned military garb.

Much of the ceremony touched on the Black military experience. A World War II soldier, Private Spicely was shot in uniform after leaving Camp Butner to visit the Hayti neighborhood of Durham on July 8, 1944.

“Since this country has been a country, Black men and later women have answered the call when this country went to war,” said attorney James Williams, chair of the Booker T. Spicely Committee.

“[Spicely] answered the call to serve a country that didn’t always serve him,” said Colonel Larry E. Campbell, a retired United States Army officer.

Speakers also highlighted the importance of bringing Spicely’s story into the classroom — especially as policymakers across the country are prohibiting schools from teaching about systemic racism.

“We need young folks who can analyze the root causes of today’s problems, who can formulate informed opinions based in fact. We need future leaders who can determine creative solutions,” said Christie Hinson Norris, director of Carolina K-12, a public humanities program at UNC-Chapel Hill.

“We are not going to motivate young folks to step up and lead when they’re only learning a watered-down version,” Norris continued. “We can only inspire young folks if we teach the truth.”

The crowd resembled a church congregation, occasionally chiming in with a chorus of “yeses.” Some attendees rang their bicycle bells in harmony.

The ceremony concluded with the unveiling of the historical marker. A group of Spicely’s relatives did the honors, pulling off a black sheet to reveal the placard.

Many of the attendees then headed into a dedication ceremony in an auditorium at the North Carolina School for Science and Mathematics, the former site of Watts Hospital. Spicely was denied medical care at the hospital following the shooting because of his race, and he was later pronounced dead upon arrival at Duke Hospital. Spicely’s killer, bus driver Herman Council, was acquitted by an all-white jury after only 28 minutes of deliberation.

At the ceremony, a simple, black-and-white portrait of Spicely in his military uniform was projected onto the screen. Audience members heard from Cynthia Mitchell, whose mother was Spicely’s first cousin. The dedication also included musical performances from the NCSSM Colours Gospel Choir and Mary D. Williams, a gospel singer, historian and educator.

The keynote speaker was Margaret Burnham, a professor at the Northeastern University School of Law who serves on the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board, an agency tasked with investigating unsolved murders of Black Americans.

“We remember the past through this marker for all Booker Spicely endured,” Burnham said. “And because it’s our pledge that as we recover, recuperate, and revive our country’s history, every inch of it, we won’t sanitize it, but we will tell it.”

As audience members exited the auditorium, they were greeted by the music of Florence Price, a Black composer.

“It’s just really exciting to finally see this and finally see the Department of Cultural Resources change enough to really be embracing stories like this and putting Jim Crow on a historic marker,” said Barbara Lau, who attended the unveiling and dedication ceremonies. “They’re moving in the right direction.”

Above: Photos by Mia Penner — The 9th Street Journal

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misidentified a speaker at the installation ceremony. The story has been updated to correct the error.