As about 80 people settled into their seats in the airy auditorium at the Durham County Library, Eddie Davis, a former City Council member and longtime teacher, scanned the crowd.

Davis asked how many in the audience weren’t in Durham in 1986. Nearly half of the hands in the room shot up. Davis nodded, acknowledging that many in the audience had no firsthand knowledge of the events that unfolded that year.

At the far end of the panel, former Durham Mayor Wib Gulley adjusted his plaid shirt as he prepared to recount the fight that nearly cost him his job.

‘The reaction was huge’

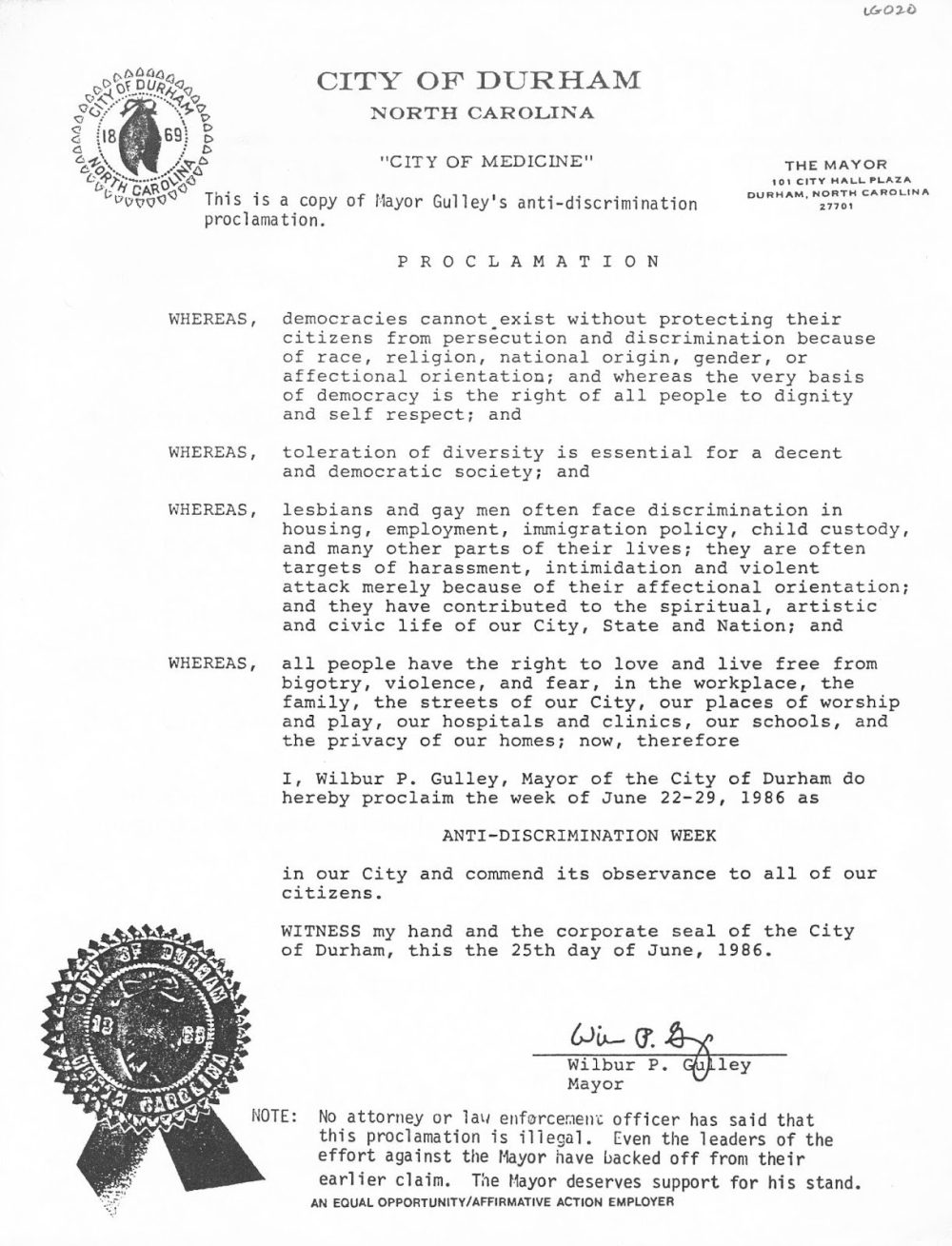

Leaders from a defining moment in Durham’s history gathered at the library on Jan. 25 to discuss the city’s first gay pride march and the political battle that erupted around it. The event brought together longtime activists, former city leaders, and community members who lived through 1986, a year when Durham found itself at an unexpected crossroads. That summer, when Gulley signed an anti-discrimination proclamation, a fierce backlash followed. More than four decades later, those who fought that backlash reunited — a brain trust of Durham’s past leaders — to reflect on the lessons it holds today.

“To me, the story of the recall and its defeat is the story of that door, that portal, that opening, when a community decides to stand up for itself,” Mab Segrest, a longtime activist and panelist, told the audience.

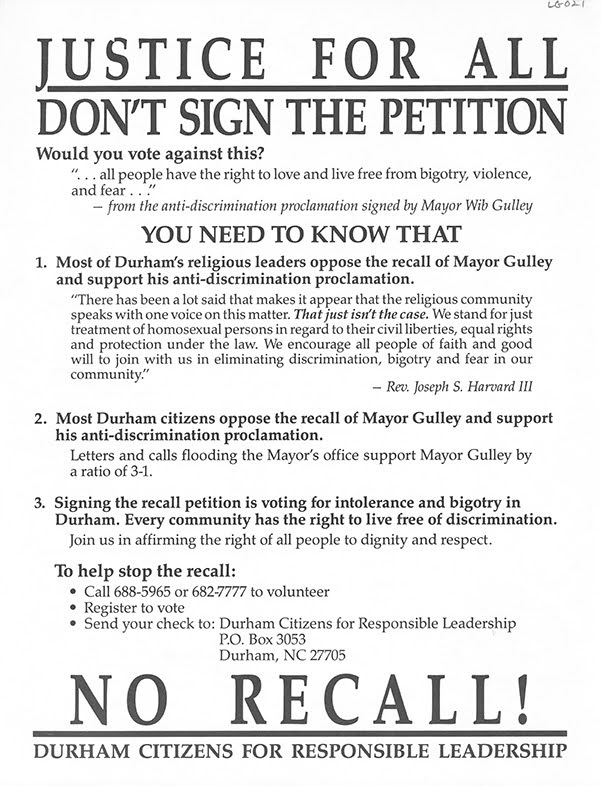

What began as a grassroots effort to organize a Pride march escalated after Gulley signed a proclamation affirming Durham’s LGBTQ+ residents. A coalition, including some conservative religious leaders, launched a campaign to recall him.

“Nobody quite anticipated the reaction,” Gulley said in an interview afterwards. “But the reaction was huge.”

“It captivated the community,” Gulley said.

For weeks, the recall consumed the city. Letters to the editor flooded Durham’s newspapers. Tables popped up across the city — some collecting signatures to demand Gulley’s removal, others mobilizing to defend him.

“How did Durham become what it is today?” Gulley said. “I think more than anything else, the story of what happened in summer in 1986 was the key, pivotal point.”

Crossing a line

Meredith Emmett, now a nonprofit leader, was a young activist in 1986. She recalls hatching plans for a Pride march in Durham over a potluck dinner. It was a different city then.

“When I first came to Durham, the tobacco factories were still operating downtown,” she said in an interview. “There was a very active Ku Klux Klan presence.”

She and her co-organizers planned strategically. They trained peacekeepers for the march, built alliances with other progressive groups and asked Gulley to sign a proclamation to get a prominent politician to take a stance.

Gulley was glad to sign it. “It was not something I thought about for three seconds,” he said.

The Durham Morning Herald weighed in even before Gulley signed. A few days before, the paper’s lead editorial read, “There is a fine line between showing the courage of one’s conviction and brain damage. Mayor Wib Gulley is about to cross that line.”

Echoes today from a moment in 1986

“First of all, we thank you for crossing that line and showing the courage of your convictions,” panelist Steve Schewel, a former Durham mayor and co-founder of The Independent, told Gulley, leaning towards him at the far end of the panel.

Schewel compared the backlash to Gulley’s 1986 proclamation to today’s attacks on gay rights.

“This editorial isn’t just a reasoned disagreement about policy; it’s a screed, an angry, hate-filled yelp that reminds me of the language that we read today in the attacks on trans people and their allies and advocates,” he said.

“The far right always aims to hate somebody. And now it’s our trans friends and neighbors, our immigrant friends and neighbors, and our refugee friends and neighbors who are bearing the brunt of this vitriol.”

For Schewel and other panelists, the recall fight wasn’t just about one mayor’s decision — it was Durham choosing what the city would be. Organizers who opposed the recall built coalitions across racial and political lines. Reverend Joe Harvard, former pastor of First Presbyterian Church, recalled how faith leaders joined the fight. Activist and scholar Leah Wise spoke about engaging Durham’s Black community in LGBTQ+ rights.

Resistance played out everywhere — petition tables, radio ads and door-to-door mobilization.

“No one part of that alliance could have defeated the recall,” Emmett said in an interview. “Joe Harvard couldn’t have done it alone. The People’s Alliance could not have defended their candidate that they had elected to be mayor. They needed other alliances.

“White people couldn’t have done it alone. The gay and lesbian community certainly didn’t have the political strength to do it. It was all of those alliances that made it possible.”

For Schewel, that moment in 1986 carries eerie echoes today. For instance, he mentioned the Idaho legislature’s recent call to repeal laws granting marriage equality for same-sex couples.

“Even victories that we thought were secure are endangered,” Schewel told fellow panelists.. “We know what happened with Roe v. Wade, how the right to reproductive freedom was taken away. And so we have to be concerned that these other rights are under fire and we need to work hard to make sure that they’re protected.”

“I don’t believe that will happen,” he added. “But I think of the effort to recall Wib in 1986, the Pride March that took place amidst this political turmoil, and the organizing to stop the recall as a time of danger—danger to live as an elected official, danger to our vision of progressive Durham, and danger most of all to our LGBTQ+ residents.”

The recent panel is part of a broader effort to document Durham’s history from that summer. Gulley started the project three years ago when he connected with Duke professor Andrew Nurkin and UNC-Chapel Hill Ph.D. student Hooper Schultz to compile archival materials and conduct oral histories.

This year, the group plans to launch an exhibit with the Museum of Durham History and work toward producing a documentary on the recall battle.

“How can Durham’s past help us stand up for justice today?” Gulley said afterwards. “The recall battle can help us face some of the threats of bigotry and intolerance that are out there.”

‘A town willing to have public conversations’

In the end, the 1986 recall effort failed. Organizers couldn’t gather enough signatures to force an election.

“That was seen as a pretty stunning result,” Gulley said. “Ordinary people stood up and said, ‘No, that’s not who Durham is, and that’s not what we’re gonna be or want to see this community be. We want to take a different path.’”

While Durham now has a reputation for progressive policies, that wasn’t the case in 1986.

He said that in the 1970s and early 1980s, many saw the city as conservative and resistant to change. “Everybody, both in and surrounding Durham, in the state and the region, thought of Durham as this blue-collar, predominantly white, conservative, rednecky place.”

But 1986 proved otherwise. Gulley said it helped shape the city’s identity as one that prides itself on inclusion.

On June 28, 1986, the Triangle Lesbian and Gay Alliance held Durham’s first annual pride march with the theme “Out Today, Out to Stay.” According to a Durham County library history exhibit, up to 1,000 people marched from Ninth Street to the Durham Reservoir on Hillsborough Road.

As years passed, Gulley realized how little-known the recall battle had become. “I began to realize about three, four years ago,” he said. “The stuff that may have had a real critical impact on how things turned out can get lost in the sands of time.”

Now 76, he hopes to pass the story on to younger generations.

“It was good not just for people who were gay or lesbian in Durham. It was good for everyone in Durham,” Gulley said. “It’s certainly a story that I don’t want Durham to forget, but for better or for worse, it’s a story that has great relevance to urban communities all over America today.”

Emmett agrees. For her, one lesson of that moment is the power of alliances. “We’re always stronger together. No one piece of any alliance can win on big issues. You’ve got to work with other people, and they may be people you don’t agree with on everything, but you agree on something, and you work together on that something.”

Another lesson of 1986, Emmett said, is about honest conversations.

“We are a town willing to have public conversations about who we want to be,” she said. “What was so evident from that 1986 story is how much we used to have those conversations.”

“That ability that we will have public conversations has been and is a really important part of who Durham is.”

Above: A scene from Durham’s first Pride march in 1986. Photo courtesy of the Durham County Library (Meredith Emmett Papers, LGBTQ Collection, North Carolina Collection, Durham County Library: https://durhamlgbtqhistory.org/exhibit/decade/the-1980s.html).