When Nicole Elliott met Shajuan Ervin in the spring of 2017, she liked him.

Ervin, her daughter Kira’s boyfriend, was a senior at Elizabeth City State University, Elliott’s alma mater, a soccer player who called her “ma’am” when they ran into each other at the store.

Now, Elliott does not like to say Ervin’s name. Instead, she sticks to pronouns or calls him “the person:” “the person” who, in the early morning of March 19, 2019, held her granddaughter in one arm and loaded a gun with the other; “the person” who, in a fit of rage, shot her son and killed her son Marcus that same day.

July 12 marks the fifth year that Elliott will celebrate her son’s birthday without him. Since his death, she has worked to help other mothers heal their grief. Her nonprofit, the Marcus Jackson Project, provides support to those who have lost loved ones to violence. Many of them are mothers, like her.

Tensions End in Tragedy

In 2018, Ervin, Kira and Marcus were all living in Durham. That fall, Ervin and Kira gave Elliott her first granddaughter, Lu. In December, Elliott wrapped toys for the baby girl to open on Christmas morning.

Elliott defended Ervin to family members who somehow sensed the young man was troubled. Elliott trusted her daughter’s judgment. And if Ervin was crooked, she thought, enough time spent with her family would straighten him out.

Elliott’s oldest son, Marcus, was the most vocal about these concerns. After Marcus got a job at Walmart Automotive in Durham, he, his girlfriend, and their son Ma’Khai moved into an apartment in the city with Kira and Ervin.

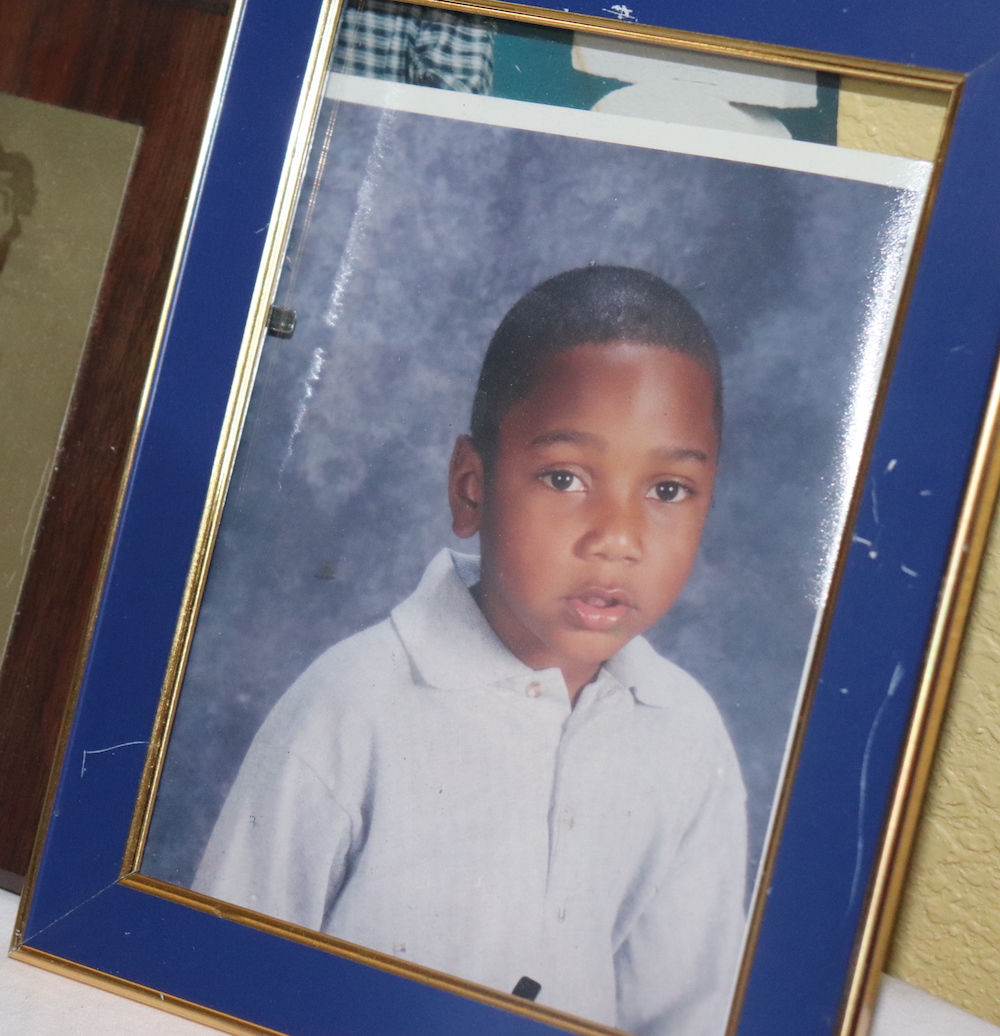

Marcus “Sno” Jackson had recently graduated from trade school and was pursuing a career in auto mechanics. High school teachers and classmates coined Marcus’s nickname on the football field, where he physically dominated opponents but maintained a “chill,” collected demeanor. After games, family and friends always found him with a wide, goofy grin.

Marcus, then in his early twenties, took his roles as big brother and father seriously, often assuming the lion’s share of household responsibilities. He mastered getting Khai and Lu to fall asleep simultaneously and enjoyed taking his son and Ervin’s son for haircuts.

But tension in the household was growing. It worsened when Ervin’s younger sister moved in without contributing financially. Marcus described the worsening tension to his mother and reported that Ervin cheated with other women and was “brainwashing” his sister.

Though he did not like Ervin, Marcus tried to be a peacemaker. After an argument on March 18, 2019, Marcus purchased a whole chicken to cook for the family. His peace offering didn’t have the effect he hoped, though. As the night wore on, tension mounted in the household.

Early the next morning, March 19, Ervin shot Marcus and Marcus was rushed to the emergency room.

‘Knowing Someone Cares Can Save a Life’

Elliott created the Marcus Jackson Project in September 2019 to help her and others heal. Based in Edenton, North Carolina, the project provides support—listening sessions, cooking classes, and mentorship—to those who have lost loved ones to violence. Every year, the organization hosts two barbeques—one on July 15, Marcus’ birthday, and the other on March 19, the anniversary of his passing. She reflects on what gun violence prevention should look like in North Carolina.

“If we show the people that we value them, they will begin to value themselves, and then they will value their community,” said Elliott. “So, just knowing that someone cares can save a life..”

Elliott tries not to blame herself for how things unfolded in her son’s household. The morning before Ervin attacked Marcus, she ranted to her son about how Ervin had become increasingly disrespectful.

“Even now, sometimes I wonder if I didn’t fuss at him [Ervin] at the end. If I had shown him more compassion… maybe that would have changed the trajectory of things that day. So I have to take accountability,” Elliott said, giving a tight-lipped smile that barely revealed the gap between her front teeth. Then, she paused and reevaluated the events of that night.

“But, at the end of the day, none of us had the gun in our hands,” she added, watching the ceiling through glassy eyes.

Elliott, 45, spent most of her life in Edenton, North Carolina, a town of barely 5,000.

While the coastal city draws hundreds of tourists yearly, Elliott cared little for her town’s history or architecture as a child. She loved the people.

Growing up, Elliott’s grandmother taught kindergarten out of their family home in the historic downtown area where Elliott lives today. She remembers riding her bike with other children up and down the block. There was always something to do back then because parents were not afraid to let their children go outside, she said. Though the neighborhood kids fist-fought, the environment was not as dangerous as today, she added.

“We would fight on Tuesday, and by Friday, everybody was hanging out and going to the movies together,” Elliott said. “Now, …every time you turn on the TV or check social media, you see children shooting or stabbing.” Until Marcus’ death, gun violence had not directly touched Elliott’s life.

‘Grief is Just Love You Don’t Know What to Do With’

Immediately before and after the shooting, Kira called her mother in a panic. Elliott instructed Kira to hang up and call 911. As she dressed her youngest son Amaree for a 160-mile drive to Durham, she prayed that Marcus would be okay.

“When your children need you, you don’t think about the details,” Elliott said. “I knew I was going to Durham and would figure out the rest when I arrived. I did not think he would be gone when I got there.”

Elliott ended up in the lobby of a Duke Hospital emergency room, clutching her older brother and her 11-year-old son close.

Though much of that morning is foggy for Elliott, she remembers pleading with the receptionist to see her son as he lay in his hospital room dying.

“I begged to just put my eyes on him,” she said. A spokesperson for Duke Health declined to comment on Elliott’s case, citing HIPAA patient privacy regulations.

According to a 2023 study, from 2019 to 2021, Durham saw 771 shooting victims—111 of whom died. In 2019, the year that Marcus died, 189 residents were shot. The numbers have remained high since then, with 289 shootings in the first half of this year.

Although Edenton is significantly smaller than Durham, about 18 residents fall victim to violent crime each year. After Marcus’ death, Elliott began recognizing how often this occurred—even in her seemingly quaint hometown.

When Elliott, a licensed therapist, saw the names of gunshot victims televised or published in the local paper, she made a habit of looking up their families on Facebook. Still grieving herself, she sent dozens of messages to mothers and other surviving family members. Elliott wanted to let them know they were not going crazy, even when it felt like they were. She reminded them that they were not alone.

In July 2019, she hosted the Marcus Jackson Project’s first “Sno Day,” celebrating Marcus’ 24th birthday without him. At the time, it was only a small gathering of friends and family. The organization officially became a nonprofit the following September.

One of Elliott’s goals with the project is to develop better services for victims in her hometown. She said her interactions with ministers and activists from the Religious Coalition for a Non-Violent Durham (RCND) and the Durham District Attorney’s office during Ervin’s 2022 trial inspired her to want more for victims in Edenton.

“The support was necessary because they ensured we didn’t have to worry about the small things. They kept reminding me, ‘We’re gonna go to trial, but a verdict won’t bring Marcus back.’.”

During the trial, the Jackson family lived in a Durham hotel, which she said the county District Attorney’s office covered. RCND staff also escorted her family in and out of the courtroom for recess.

After almost four weeks on trial, the court found Shajuan Ervin guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced him to life at Central Prison in Raleigh. But Elliott knew the trial’s ending could not be Marcus’s.

“Marcus would always tell me that he would be famous one day. So, one of my biggest fears was that people would forget about my child,” Elliott said.

“I learned that grief is just love you don’t know what to do with. Although Marcus isn’t physically here, I am still his mom, and I still have my love for him. I had to do something with that.”

‘Breathing Life into Marcus’

On a cloudy Saturday morning in March, The Marcus Jackson Project, staffed by Elliott and her family, served fried fish plates to locals at Waterfront Park in Edenton. For a $10 donation, supporters received a styrofoam container with two pieces of fish and sides.

Adults danced to old-school R&B songs broadcast over a speaker; Elliott’s grandchildren stuffed their mouths with hush puppies before swinging on nearby playground equipment. The wind rattled and ripped raindrop-stained plastic orange tablecloths (the color representing the national fight against gun violence).

By late afternoon, the muddy park began to dry as Elliott watched over the event. Occasionally, she strayed from the fryers to hold hands with the toddlers near the playground.

Elliott’s coworkers, Traniqua McCullen and LaToya Simpson, stopped by around 4 p.m. They said they watched Elliot’s lifestyle change after Marcus died.

“We knew how important her kids were to her from day one,” said Simpson. “And they knew how important they were to her. Anything they had at the school—she was always there.”

McCullen remembered nights she joined Elliott for Marcus’ football games at John Holmes High School, the only high school in the city. As the sun peeked through the clouds, she laughed, remembering the time the teenage charmer stole her number from his mother’s phone and texted her unexpectedly.

“He loved to joke,” McCullen said. “His legacy is known, and she played a big part in it.”

The Marcus Jackson Project sold about 40 pre-paid plates via email and Facebook ahead of the event and another 40 to passersby on the day, raising about $650.

“It is difficult to do this work because I’m not just doing it for the sake of it. I’m doing it because my son isn’t here,” Elliot said. “At the same time, though, the project gives me something to pour my energy into. I breathe life into Marcus every time I say his name.”

It has been challenging to get city leadership to recognize the need for victims’ rights and violence prevention work, Elliott said. She worries that the town is more concerned with its appearance to visitors than its lost lives.

Ideally, the Marcus Jackson Project would dispatch counselors, case workers, and drivers to support families after an act of violence. Elliot expressed pride that this year, the mayor of Edenton and council members have begun to attend Marcus Jackson Project programming.

Finding Justice

Thanks to the funds raised from the fish fry, the project’s website went live in April. Elliott, busy balancing a nine-to-five with babysitting her grandchildren, has struggled to find time to update the site with information on “Sno Day 2024,” scheduled for next week. She looks forward to expanding the project’s reach and hopes the program could someday become a model for other small towns and grieving moms.

Elliott no longer sees justice as something to gain retroactively. Instead, she believes justice happens when we keep communities safe.

“The system has fooled us into thinking that there’s justice for our murdered sons and daughters….,” she said.“Justice would be my baby coming home, dapping up his little brother, and attending his son’s basketball games. Marcus doesn’t get to do any of that.”

Despite her heartbreak, Elliott said she tries to lead her life with love. In 2020, she earned a master’s degree in social work. The following year, she married. Every day, Elliott pushes forward for other mothers—and for her kids who are still here.

Marcus’ younger brother, Maree, now 16, has his older brother’s face and voice. In the uphill battle of getting Maree to school on time, Elliott is reminded of the early morning spats she once had with Marcus. She knows that the two would have been tight.

And as for Ervin?

“He is a non-factor in my life. I realize that harboring anger toward him pulls the energy I’d rather use to honor my child,” Elliott said.

“He can’t win twice.”

Pictured above: Nicole Elliott pauses for a moment of rest during a recent Marcus Jackson Project fundraiser. Photo by Akiya Dillon — The 9th Street Journal

Akiya Dillon