On a humid Tuesday evening in July, more than 150 baseball fans sit scattered across the stands of the Historic Durham Athletic Park. Grandparents, families and toddlers have flooded through the old gates to watch the Rockhounds and Thunder go head to head.

Sweltering in the heat, boys 13 to 15 years old take turns at the plate. Their coaches are volunteers in the Long Ball Program, part of a Major League Baseball youth outreach initiative. A crack of a bat echoes out into the downtown neighborhood as the Rockhounds make a daring run to first base.

Durham Athletic Park — the DAP — was the home of the Durham Bulls from 1926 to 1994. A block away from Durham Central Park, the ballpark famously served as the backdrop for the 1988 movie Bull Durham, a romantic ode to baseball that helped put this little Southern city on the map.

The team’s popularity exploded in response to Kevin Costner and Susan Sarandon’s saucy depiction of minor league baseball. In 1995, the Bulls moved a few blocks south to their newly constructed Durham Bulls Athletic Park (DBAP), where the team still plays today.

The DAP remained standing but was poorly maintained until its renovation in 2009. Then the old park found new life as the home field for the N.C. Central University Eagles — but that era came to a close this year when NCCU, citing COVID-related budget cuts, eliminated its baseball program.

With the primary tenant gone and the surrounding downtown Durham rapidly developing, many wonder what lies ahead for this old ballpark.

The DAP remains full of life this summer, hosting several youth league games each week. The Bulls — who manage their old park under contract for its owner, the city of Durham — are optimistic about its future. The ballpark’s next era remains unclear, but city leaders say plans are forming and the DAP is here to stay.

The story of Durham Athletic Park is a story of resilience, constant evolution and, above all, a love of baseball.

Worth a run in the bottom of the ninth

For nearly a century, the DAP has stood unmoving as the city of Durham grew and evolved around it. The occupants are always changing, but its concrete walls remain impervious to the ebb and flow of time.

No matter what, the DAP endures.

It was known as El Toro Park when the Durham Bulls played their first game there in 1926. The stadium was renamed Durham Athletic Park when the city purchased the property in 1933. After a few years of vacancy during the Depression, in 1939, the DAP’s wooden grandstand burned to the ground, with the groundskeeper barely making it out alive. It was quickly rebuilt, this time with steel and concrete.

In 1951 the DAP was the backdrop for Percy Miller Jr.’s debut as the first black baseball player in the Carolina League. The Bulls played off and on there until 1972, when the team folded.

Then in 1980, owner Miles Wolff revived the Durham Bulls, filling the ballpark with 4,418 fans the first night. In the steaming North Carolina summers of the 1980s, the DAP was the place to be. Retired sportswriter Kip Coons, who covered the Bulls for the Durham Morning Herald (and who appears in Bull Durham), remembers the DAP in its prime.

He recalls a deafening roar in the small stadium, with fans shouting at the players on the field when they weren’t playing up to snuff. With a narrow foul territory and a field-level press box, the DAP was an intimate ballpark.

Regularly breaking minor league attendance records, the fans made Bulls games special. Coons said his friend Brian Snitker, now manager of the Atlanta Braves, used to say that, “the crowd in Durham was worth a run in the bottom of the ninth.”

This culture was partially why Bull Durham director Ron Shelton made Durham the setting for his now-classic film. Shelton, who had played in the minor leagues himself, wanted to capture ordinary baseball in small-town America.

And as Coons watched the movie’s premiere, he knew Shelton had succeeded. The Bulls players were laughing and joking in the theater until the scene where a player was released from the team.

“It was like a church. It was so quiet.” said Coons. “Because all the players realized, ‘Damn, that could be me tomorrow. I could be out of baseball.’ And when they reacted like that, I realized at that moment, Ron Shelton has nailed it.”

Bull Durham’s authenticity made the film a national hit, grossing $50.8 million and earning recognition as one of the best sports movies of all time. It helped revive minor-league baseball as a nationwide pastime and “shot Durham into national consciousness,” said Susan Amey, president & CEO of Durham’s tourism marketing agency, Discover Durham.

Suddenly, everyone wanted to see the Durham Bulls play, and the team began to outgrow the aging DAP. In 1990, a crowd of 6000-plus had the venue bursting at the seams.

When Jim Goodmon bought the Bulls that same year, plans for a larger ballpark were announced. The team played its first game in the new Durham Bulls Athletic Park in 1995, and three years later, the Bulls became a Triple-A minor league team — the highest before the majors.

The city began to blossom, too.

“I think Durham’s financial and cultural renaissance directly results from the Bulls’ success as a minor league franchise,” Coons said.

The Durham Bulls Athletic Park was one of the first visitor features downtown, along with Brightleaf Square, the American Tobacco Campus, and the Durham Performing Arts Center, Amey said. The restaurants, hotels, and shops were quick to follow.

As the team moved on to bigger and better things, the DAP was mostly forgotten. After the Bulls’ departure, the old park was used occasionally for festivals and softball, but the facility was rundown and the field poorly maintained.

In 2009, as a part of a broader move from the city to improve its facilities, the city gave the DAP a $5 million facelift. Renovations were done to improve the structure, surplus seating was removed, and the field was restored to a professional level playing surface.

Minor League Baseball operated the refurbished stadium for a few years as a training area for umpires and groundskeepers. Management, paid for by the city, was passed in 2012 to the Durham Bulls, who remain dedicated to the space.

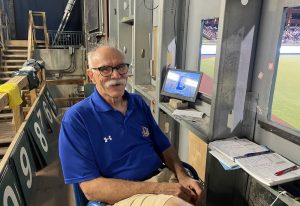

“We kind of consider ourselves caretakers of the museum, so to speak,” said Scott Strickland, who manages the DAP for the Bulls. “And that’s a lot of responsibility, but it’s a whole lot of fun, too.”

Old park, new life

NCCU’s baseball program revived the Historic DAP, bringing life and a full schedule to the venue for more than a decade. The Eagles’ daily practices and games occupied most dates September through November and January through May. The team’s final regular season game on home turf was a 6-1 victory over Florida A&M on May 15.

That would have been a pretty full calendar for a normal field, but due to the few baseball stadiums in the area, the demand for the space was high, so Durham School of the Arts and Voyager Academy also play several games there each year.

In summer, the DAP schedule is packed with youth games.

“I’d say we have activity in the ballpark six days a week,” said Joe Stumpo, the DAP’s head groundskeeper. The ballpark hosts traveling youth teams that play four games a day Thursday through Sunday. The rest of the dates are filled by the Long Ball program, a youth league that provides an alternative to expensive travel teams.

For youth leagues, the historic nature of the DAP continues to draw in a younger generation.

“I think that’s why we get so many more people coming,” said Patricia James, founder of the Long Ball Program. “That is our drawing card. When they find out this is our home field.”

The view from the stands isn’t bad, either.

“I guess it’s neat for me to see my son play on a field that Hall of Famers have played on,” said Courtney Smith, mother of 14-year-old Bryce. Smith attended Bulls games here as a kid, so “it’s a lot of younger memories that come back” when she visits the park.

Strickland was sad to see NCCU ending its program, but he isn’t worried about filling the new hole in the DAP schedule.

To Strickland their departure just means the next evolution of the DAP. While the venue has always been able to host non-sporting events, from dance recitals to Mayor Bill Bell’s retirement, the building constraints and field protection made them quite expensive and hard to squeeze into the calendar.

With NCCU off the schedule, “We’ll be able to be a little more selective on the type of events that we do,” he said. Strickland envisions it will look more like a normal baseball field schedule peppered with concerts, movies and other non-sporting events.

City leaders are ready for the DAP’s next evolution as well.

“We want to increase its usage. But we are in the early stages of thinking about that,” Mayor Steve Schewel said. He sees it as a “fantastic public asset” that ought to be used by more of the Durham community. Conversations between the city and Durham Bulls are in their infancy, but Schewel said new information should be available in a few months.

A piece of Durham’s soul

While the Durham Athletic Park has witnessed almost 100 years of a morphing Durham landscape, the last 30 years have been particularly astounding.

Downtown Durham and the streets around the DAP are crowded with big apartment buildings, new nightlife, and large construction equipment dedicated to building more and more each year.

Because of the limited land available, the 5.4 acres of land the DAP occupies is valuable real estate. For reference, in 2019, a plot of 0.6 acres across from the farmers market sold for $3.3 million. Several new developments around the ballpark will begin construction soon.

The DAP is valued at $8.2 million and developers say it would surely fetch more if the city decided to sell it, but Schewel says that’s not an option. “In my 10 years on the council and as mayor, I have never heard a single conversation about selling the property. That is not going to happen,” Schewel said.

Surprisingly, some local developers agree.

“I would frankly, as a developer, be disappointed to see that go from the neighborhood,” said Ben Perry of East West Partners, the developers in charge of the Liberty Warehouse apartments up the road on Foster Street.

They see it as precious green space, a recreational amenity, and a protected view.

“Who doesn’t like to look at a baseball field at night. It’s just a beautiful view-shed with activity and life” said Paul Snow, a developer and commercial appraiser who worked on a nearby condo property.

“I think that it is such an important part of that neighborhood that nobody is wishing to see that gone,” Snow said. Perry said a place like the DAP has a different kind of value to the community. “It can’t always be measured in dollars and cents,” he said.

The truth of it is: People just love this old ballpark.

For Kip Coons, the DAP was where he learned to be a sports writer. For Joe Stumpo, it was where he had his first full-time job at 19. For Scott Strickland, it was where he watched baseball as a kid with his dad. For Courtney Smith it is where her son plays baseball with his friends.

For others, it is the background in their wedding photo, where they hit their first home run, or maybe just where they walk their dog.

“I think it’s a connection for generations,” said Stumpo “I just think this place has a lot of history to a lot of people.”

After so many years, Durham Athletic Park has firmly established itself as a part of the city’s identity.

“I think it carries a little piece of Durham’s soul in it,” said Amey. “It’s something that residents treasure.”

Places like the DAP are important to keep not just because of their history. “There are ways to preserve memories. Some of them are museums, and some are natural things like parks, and some are just living memorials like a baseball stadium,” Coons said.

When Coons stands by the old ticket booth, the memories come flooding back — from the DAP’s heyday in the 1980s, and from the movie version, too.

“If I sit here, you know, I expect to see Annie Savoy walk by.”

At the top: The Bulls are long gone and the NCCU Eagles played their last game in May, but the DAP is busy with youth baseball this summer. Ninth Street Journal photo by Grace Abels

Grace Abels